| Brightline Ridership and Revenue Study |

|

| Phase I Study: Southeast Florida and Orlando Phase II Study: Extension to Tampa |

|

| September 2018 |

Disclaimer

This Report was prepared by The Louis Berger U.S., Inc., (LB) for the benefit of All Aboard Florida Operations, LLC (Client) pursuant to a Professional Services Agreement dated May 17, 2017.

LB has performed its services to the level customary for competent and prudent engineers performing such services at the time and place where the services to our Client were provided. LB makes or intends no other warranty, express or implied.

Certain assumptions regarding future trends and forecasts may not materialize, which may affect actual future performance and market demand, so actual results are uncertain and may vary significantly from the projections developed as part of this assignment. The data used in the Report was current as of the date of the Report and may not now represent current conditions.

The Report is provided for information purposes only. LB makes no representations or warranty that the information in the Report is sufficient to provide all the information, evaluations, and analyses necessary to satisfy the entire due diligence needs of a reader of this report.

| 1 | P a g e |

Table of Contents

| Executive Summary | 7 | |||||

| ES-1 | Overview of the Investment Grade Study Process | 8 | ||||

| ES-2 | Study Process | 9 | ||||

| ES-3 | Overview of the Brightline Rail Service | 10 | ||||

| ES-4 | Relevant Market for High Speed Rail | 11 | ||||

| ES-5 | Key Assumptions | 13 | ||||

| ES-6 | Key Findings and Ridership and Revenue Forecast | 15 | ||||

| 1.0 |

Introduction |

19 | ||||

| 1.1 |

Organization of Report |

20 | ||||

| 2.0 |

Travel Market Socioeconomic and Demographic Conditions |

21 | ||||

| 2.1 |

Population |

22 | ||||

| 2.2 |

Population Forecasts |

24 | ||||

| 2.3 |

Employment |

28 | ||||

| 2.4 |

Employment Forecasts |

30 | ||||

| 2.5 |

Income |

31 | ||||

| 2.6 |

Travel and Tourism |

32 | ||||

| 2.7 |

Domestic Visitation |

34 | ||||

| 2.8 |

International Visitation |

34 | ||||

| 3.0 |

Intercity Travel Market for Brightline |

36 | ||||

| 3.1 |

Addressable Market Geography for Brightline |

37 | ||||

| 3.2 |

Travel Market for Brightline Phase I Study |

38 | ||||

| 3.2.1 | Bus | 38 | ||||

| 3.2.2 | Long-Distance Rail (Amtrak) | 41 | ||||

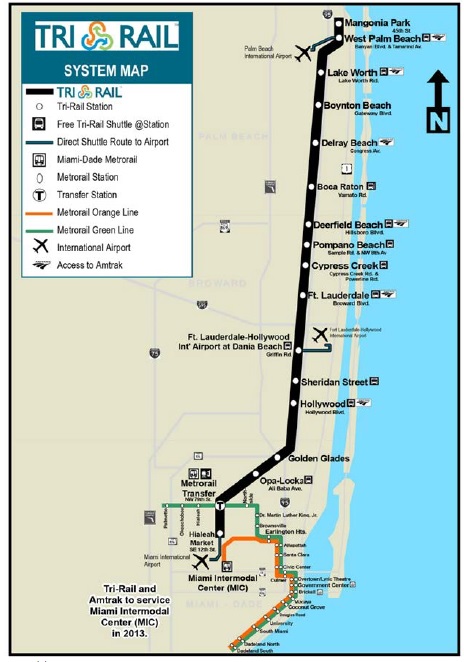

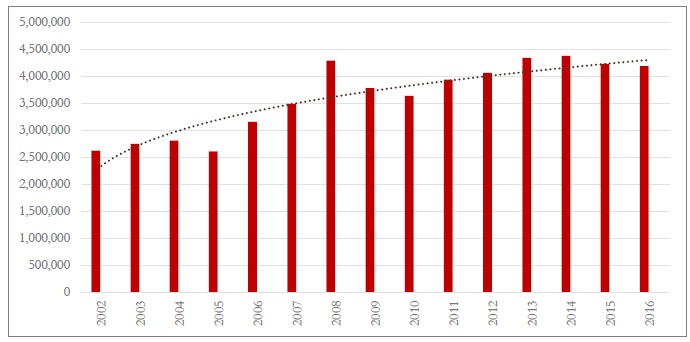

| 3.2.3 | Short-Distance Rail (Tri-Rail) | 42 | ||||

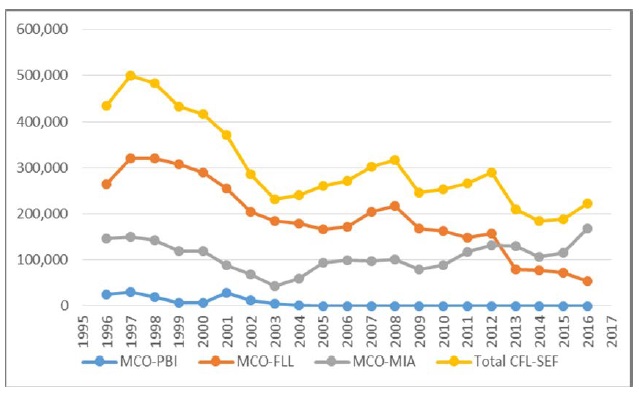

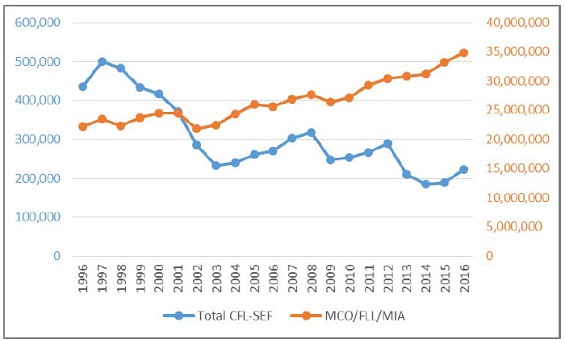

| 3.2.4 | Air | 45 | ||||

| 3.2.5 | Auto | 47 | ||||

| 3.3 |

Travel Market for Brightline Phase II Study |

54 | ||||

| 3.3.1 | Bus | 54 | ||||

| 3.3.2 | Rail (Amtrak) | 56 | ||||

| 3.3.3 | Air | 57 | ||||

| 3.3.4 | Auto | 59 | ||||

| 3.3.5 | Airport Access Trips | 64 | ||||

| 4.0 |

Brightline Travel Demand Model |

66 | ||||

| 4.1 |

Overview of Methods |

66 | ||||

| 2 | P a g e |

| 4.2 |

Survey Design |

66 | ||||

| 4.2.1 | Screening | 66 | ||||

| 4.2.2 | Reference Trip | 67 | ||||

| 4.2.3 | Choice Exercise | 67 | ||||

| 4.2.4 | Induced Travel | 69 | ||||

| 4.2.5 | Socioeconomic Characteristics | 69 | ||||

| 4.3 |

Survey Implementation and Summary |

69 | ||||

| 4.3.1 | Survey Implementation and Summary for Brightline Phase I Study | 69 | ||||

| 4.3.2 | Survey Implementation and Summary for Brightline Phase II Study | 72 | ||||

| 4.4 |

Mode Choice Model Estimation |

75 | ||||

| 4.4.1 | Conceptual Overview | 75 | ||||

| 4.4.2 | Summary of Model Estimation Process (Phase I Study) | 77 | ||||

| 4.4.3 | Summary of Model Estimation Process (Phase II Study) | 80 | ||||

| 4.5 |

Travel Demand Model Development |

80 | ||||

| 4.5.1 | Level of Service Assumptions | 81 | ||||

| 4.5.2 | Model Calibration | 91 | ||||

| 4.5.3 | Induced Ridership | 92 | ||||

| 5.0 |

Brightline Ridership and Revenue Forecast |

94 | ||||

| 5.1 |

Overall Level of Ridership and Revenue |

94 | ||||

| 5.1.1 | Ramp-Up | 96 | ||||

| 5.1.2 | Methodological Overview | 96 | ||||

| 5.2 |

Fare Revenue Estimation |

97 | ||||

| 5.3 |

Network Model Ridership & Revenue Forecasts |

98 | ||||

| 5.3.1 | Market Capture and Compatibility with Existing Modes of Travel | 98 | ||||

| 5.4 |

Overall Forecast Summary |

103 | ||||

| 5.4.1 | Forecast Growth Comparison | 103 | ||||

| 5.5 |

Segment Loading and Boardings & Alightings |

103 | ||||

| 5.6 |

Phase II Study Lakeland Station Impacts |

105 | ||||

| 6.0 |

Forecast Sensitivity |

106 | ||||

| 6.1 |

Brightline Travel Time |

106 | ||||

| 6.2 |

Brightline Frequency |

106 | ||||

| 6.3 |

Intercity Travel Time by Auto |

107 | ||||

| 6.4 |

Auto Fuel Prices |

107 | ||||

| 6.5 |

Air Fares |

107 | ||||

| 7.0 |

Conclusion |

108 | ||||

| 3 | P a g e |

| Appendix A Population Density | 109 |

| Appendix B Employment Density | 114 |

| List of Figures and Tables | |

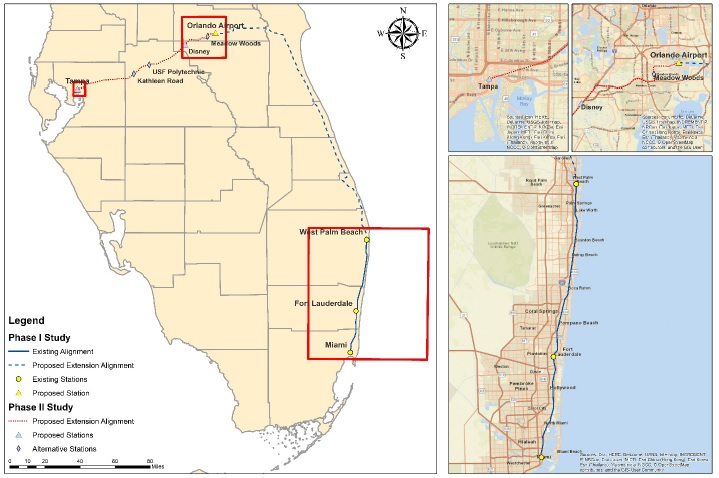

| Figure ES-1 The Study Area of Phase I and Phase II of the Study | 7 |

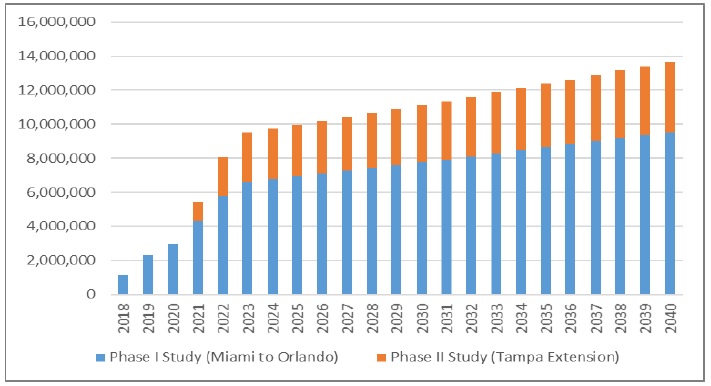

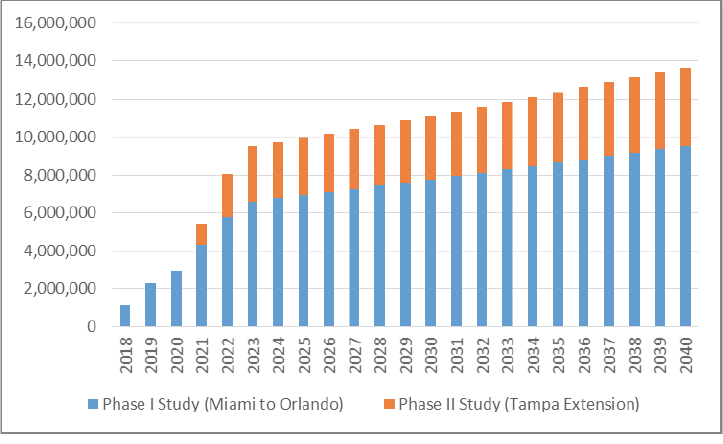

| Figure ES-2 Brightline Annual Ridership Forecast, 2018-2040 | 16 |

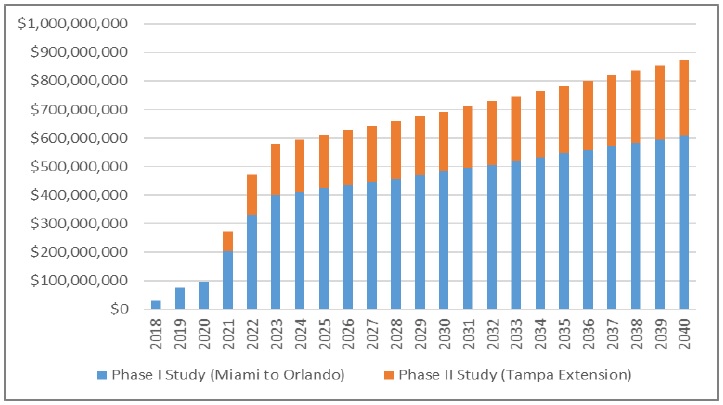

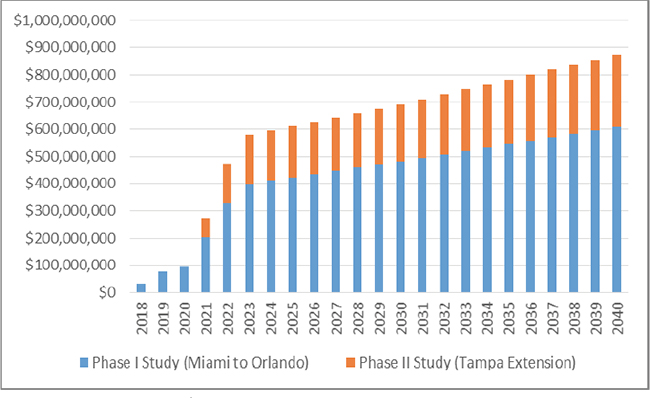

| Figure ES-3 Brightline Fare Revenue Forecast, 2018-2040 (2016 $) | 17 |

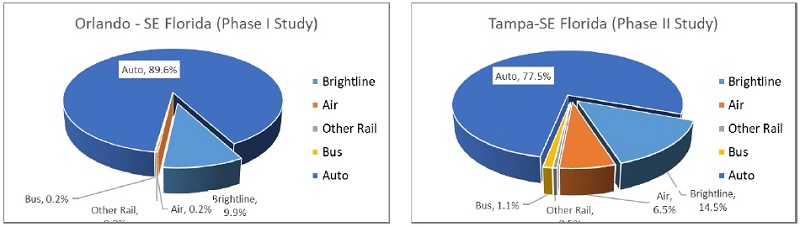

| Figure ES-4 Brightline Long-Distance Market Share, 2023 | 17 |

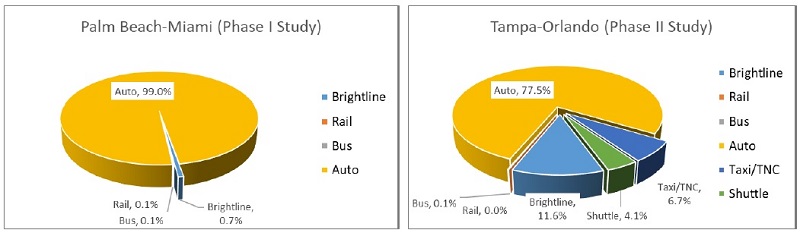

| Figure ES-5 Brightline Short-Distance Market Share, 2023 | 18 |

| Figure 1-1 Proposed Route and Stations | 19 |

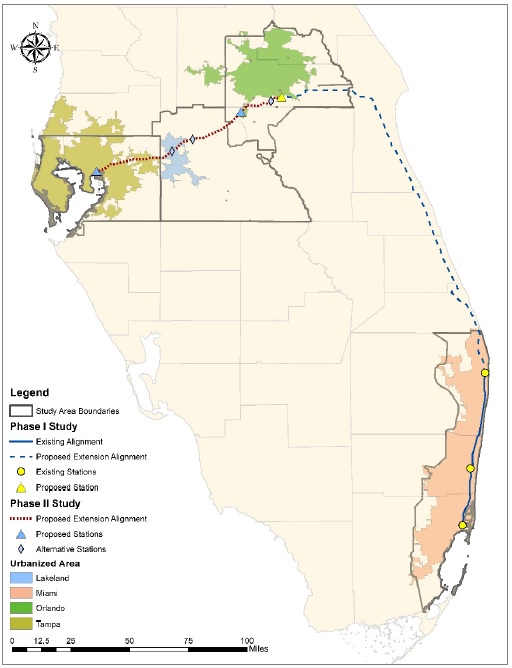

| Figure 2-1 Study Area | 21 |

| Figure 2-2 Study Area Population Density | 22 |

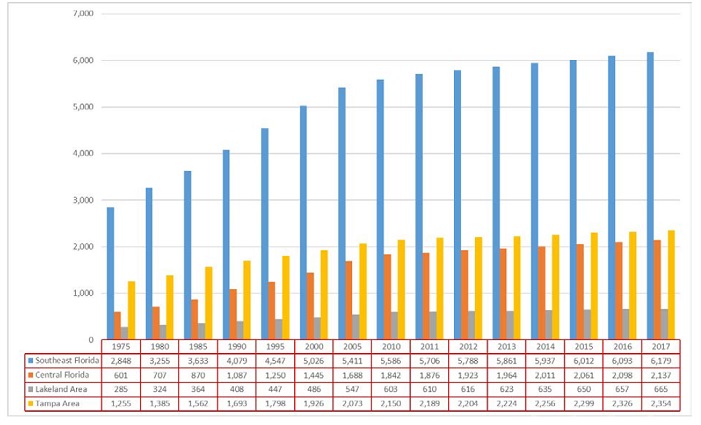

| Figure 2-3 POPULATION, 1975-2015 (IN THOUSANDS) | 23 |

| Figure 2-4 COMPOUND ANNUAL GROWTH RATE IN POPULATION | 24 |

| Figure 2-5 MPO POPULATION FORECAST BY COUNTY, 2010-2040 (IN THOUSANDS) | 25 |

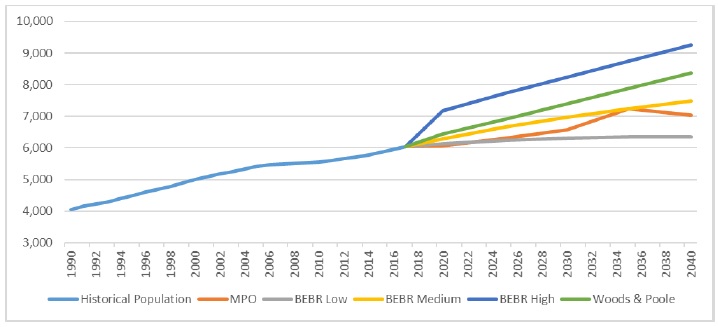

| Figure 2-6 SOUTHEAST FLORIDA POPULATION FORECAST | 26 |

| Figure 2-7 CENTRAL FLORIDA POPULATION FORECAST | 26 |

| Figure 2-8 LAKELAND POPULATION FORECAST | 27 |

| Figure 2-9 LAKELAND POPULATION FORECAST | 27 |

| Figure 2-10 Study Area Employment Density | 28 |

| Figure 2-11 Employment 1975-2015 (in Thousands) | 29 |

| Figure 2-12 Employment Forecasts by Region 2010-2040 (Thousands) | 30 |

| Figure 2-13 REAL PER CAPITA PERSONAL INCOME, 1975-2015 (2017 DOLLARS) | 31 |

| Figure 2-14 HISTORICAL TRENDS IN FLORIDA VISITATION: 2006-2015 | 32 |

| Figure 2-15 TRAVEL RELATED EMPLOYMENT IN FLORIDA | 33 |

| Figure 2-16 ANNUAL VISITATION BY THEME PARK | 33 |

| Figure 3-1 Travel Time to Nearest Brightline Station | 37 |

| Figure 3-2 Market Catchment Areas | 38 |

| Figure 3-3 Historical Growth in Intercity Bus Travel in the United States | 40 |

| Figure 3-4 Amtrak Florida Station Boardings | 41 |

| Figure 3-5 Tri-Rail System Map | 43 |

| Figure 3-6 Tri-Rail System Ridership | 44 |

| Figure 3-7 Annual Air Traffic Volume between Central and Southeast Florida | 45 |

| Figure 3-8 Comparison of Air Traffic Volumes | 46 |

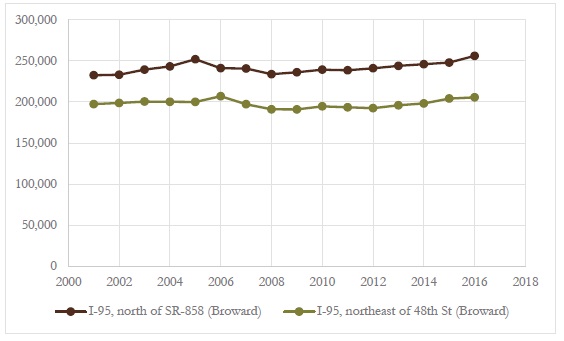

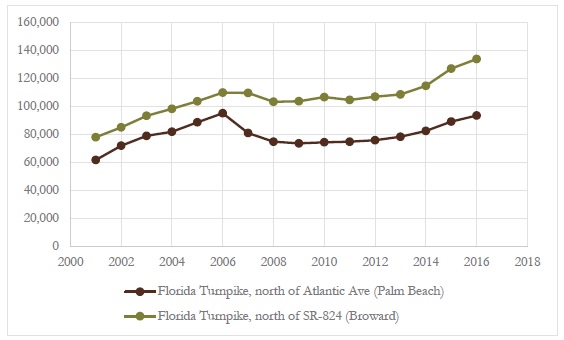

| Figure 3-9 Florida Turnpike Central-to-Southeast Florida Historical Traffic Counts | 48 |

| Figure 3-10 I-95 Central-to-Southeast Florida Historical Traffic Counts | 48 |

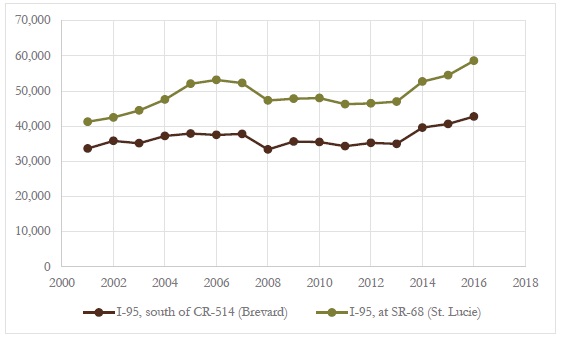

| Figure 3-11 Southeast Florida Historical Traffic Counts | 50 |

| Figure 3-12 Southeast Florida Historical Traffic Counts | 50 |

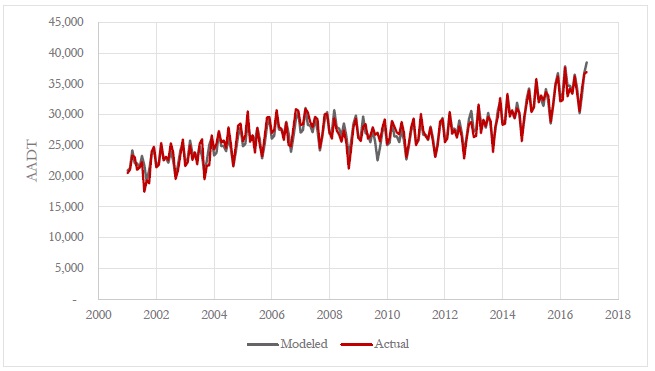

| Figure 3-13 Florida Turnpike Traffic Model Performance (Actual Vs. Fitted – Monthly) | 53 |

| Figure 3-14 Econometric Analysis and Projection of Florida Turnpike Traffic (Monthly) | 53 |

| Table 3-13 Estimated Daily Intercity Long-Distance Bus Person Trips | 54 |

| Figure 3-15 Ridership Benchmark From RSG | 55 |

| Table 3-14 Projected Daily Intercity Bus Person Trips | 55 |

| Figure 3-16 Amtrak Florida Station Boardings (Thousands) | 56 |

| Table 3-15 Historical and Future Amtrak Passenger Volumes | 56 |

| 4 | P a g e |

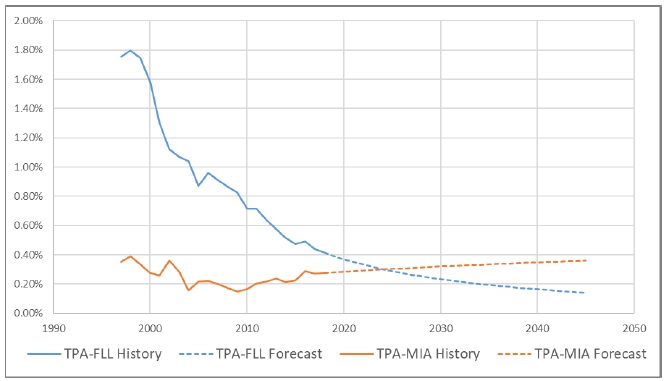

| Figure 3-17 Annual Air Traffic Volume between Tampa and Southeast Florida | 57 |

| Table 3-16 Annual Air Passenger Volumes, FAA 10% Ticket Sample | 57 |

| Figure 3-18 FAA’s Terminal Area Forecasts For Airport Enplanements In Study Area | 58 |

| Figure 3-19 Passenger Volume Share Of Enplanement In Origin And Destination Airport | 59 |

| Figure 3-20 Prediction Of Future Passenger Volume Between City Pairs | 59 |

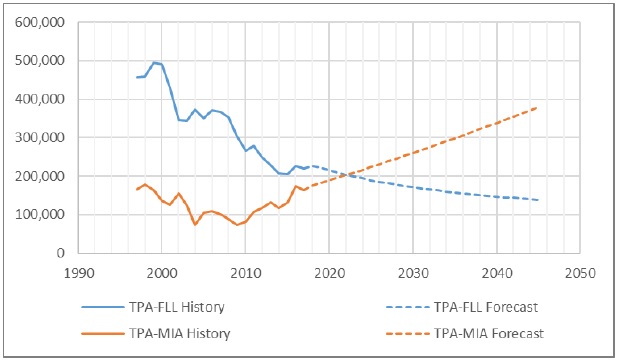

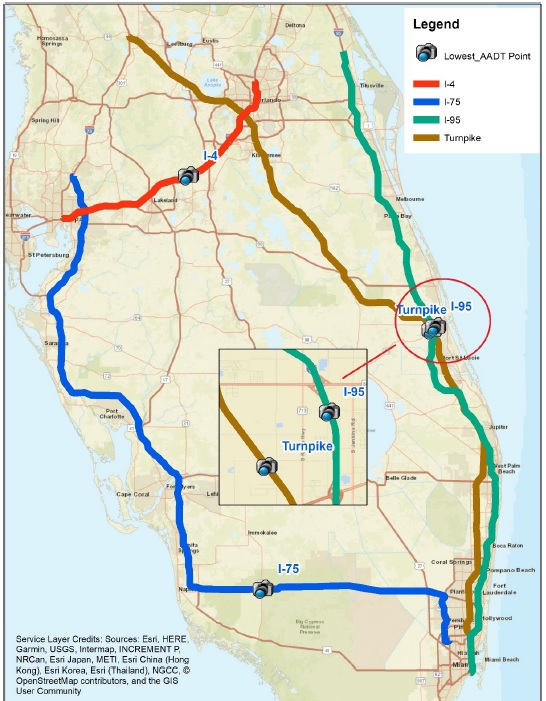

| Figure 3-21 Counter stations identified for historical traffic volume | 61 |

| Figure 3-22 Historical AADT Trend At Counter Stations | 62 |

| Table 3-17 Summary Of Historical Aadt And Cagr | 62 |

| Table 3-18 Estimated Daily Auto Person Trips By Time Of Day | 63 |

| Table 3-19 Annual Auto Person Trips Projection | 64 |

| Table 3-20 Current And Future Airport Access Choice Trips By Mode | 65 |

| Figure 4-1 Example Stated Choice Exercise | 68 |

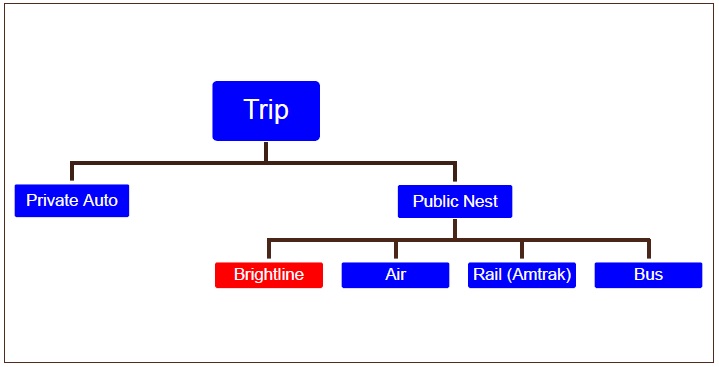

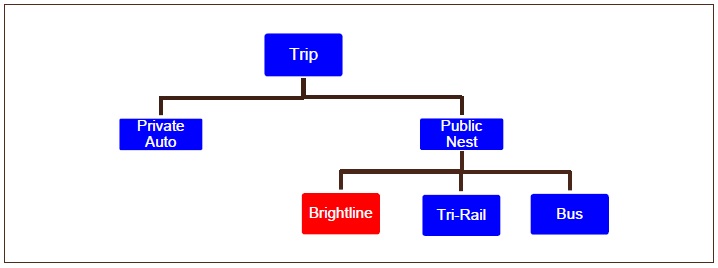

| Figure 4-2 LONG DISTANCE MODE CHOICE MODEL NESTED LOGIT STRUCTURE | 77 |

| Figure 4-3 SHORT DISTANCE MODE CHOICE MODEL NESTED LOGIT STRUCTURE | 79 |

| Figure 5-1 Brightline Annual Ridership Forecast – Base Case | 95 |

| Figure 5-2 Brightline Annual Revenue Forecast – Base Case | 95 |

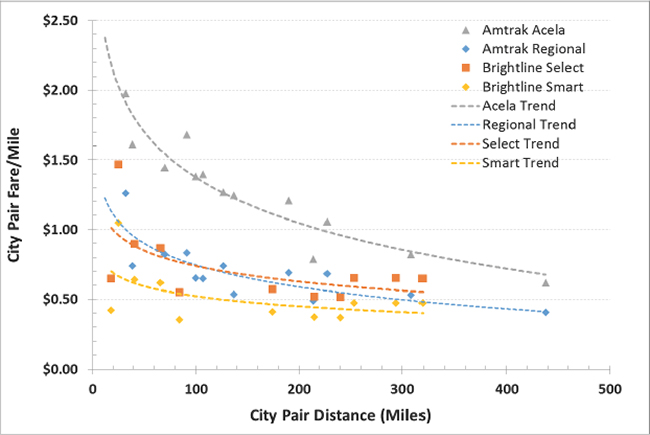

| Figure 5-3 Comparison of Brightline Fares to Amtrak Northeast Corridor Fare Rates | 98 |

| Figure 5-4 Long-Distance Travel Network Model Market Shares, 2023 | 99 |

| Figure 5-5 Share of Brightline Ridership by Source (Long-Distance) | 100 |

| Figure 5-6 Brightline Ridership Market Draw by Source (Long-Distance) | 100 |

| Figure 5-7 Share of Brightline Ridership by Source (Short-Distance), 2023 | 101 |

| Figure 5-8 Share of Brightline Ridership by Source (Short-Distance) | 102 |

| Figure 5-9 Brightline Ridership Market Draw by Source (Short-Distance) | 102 |

| Figure 5-10 Comparison of Brightline Forecast Growth Rates | 103 |

| Table ES-1 Brightline Ridership and Revenue Forecast, 2023 (2016 $) | 16 |

| Table ES-2 Sensitivity Test Results, Ridership and Revenue % Change, 2023 | 18 |

| Table 3-1 Estimated Daily Intercity Long-Distance Bus Person Trips | 39 |

| Table 3-2 Estimated Daily Short-Distance Bus Person Trips | 39 |

| Table 3-3 Projected Daily Intercity Long-Distance Bus Person Trips | 40 |

| Table 3-4 Projected Daily Short-Distance Bus Person Trips | 40 |

| Table 3-5 Historical and Future Amtrak Passenger Volumes | 42 |

| Table 3-6 Current and Projected Daily Short-Distance Rail Trips | 44 |

| Table 3-7 Annual Air Passenger Volumes, FAA 10% Ticket Sample | 46 |

| Table 3-8 Estimates of Air Passengers in the Brightline Service Travel Market | 47 |

| Table 3-9 Estimated Daily Long-Distance Auto Person Trips | 51 |

| Table 3-10 Estimated Daily Short-Distance Auto Person Trips | 51 |

| Table 3-11 Long-Distance City Pair O-D Shares | 52 |

| Table 3-12 Short-Distance City Pair O-D Shares | 52 |

| Table 5-1 2023 Ridership & Revenue | 94 |

| Table 5-2 Ramp-up Comparisons | 96 |

| Table 5-3 Average Fares (Smart Class), 2016 $ | 97 |

| Table 5-4 Average Fares (Select Class), 2016 $ | 97 |

| Table 5-5 Long-Distance Travel Network Model Market Shares by City Pair, 2023 | 99 |

| Table 5-6 Short-Distance Travel Network Model Market Shares by City Pair, 2023 | 101 |

| Table 5-7 Forecast Brightline – Annual Segment Volumes and Revenues (2016 $) | 104 |

| Table 5-8 Brightline Daily Boardings and Alightings, 2023 | 104 |

| 5 | P a g e |

| Table 5-9 Brightline Daily Boardings and Alightings, 2030 | 105 |

| Table 5-10 Lakeland Station Ridership and Revenue Impacts | 105 |

| Table 6-1 Sensitivity Test Results, Ridership and Revenue % Change, 2023 | 106 |

| 6 | P a g e |

Executive Summary

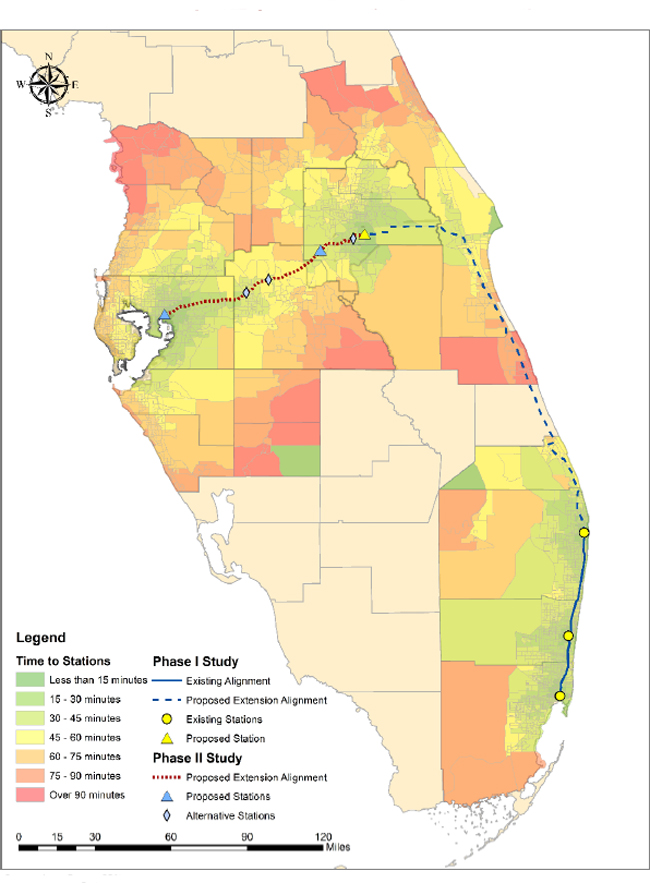

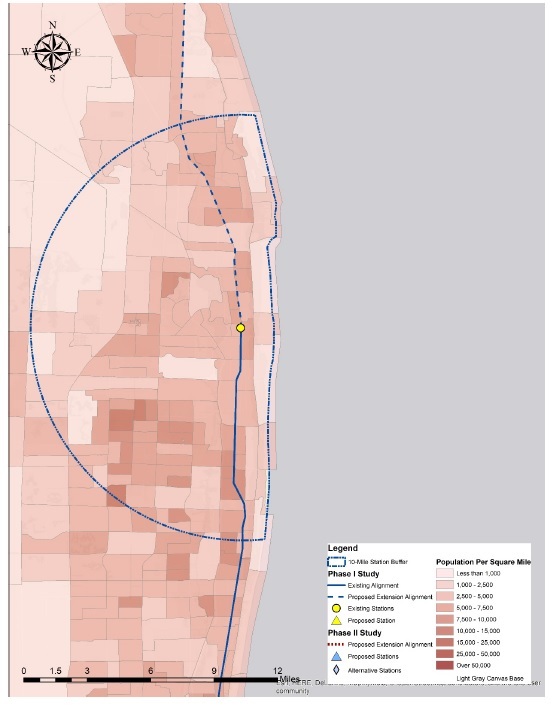

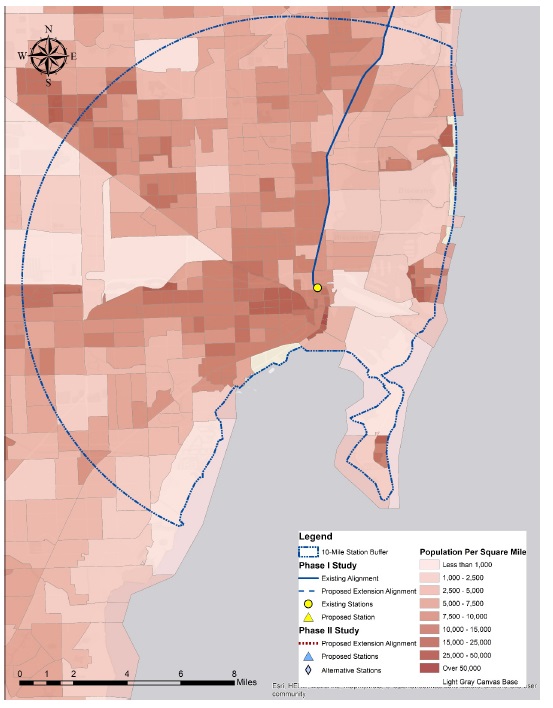

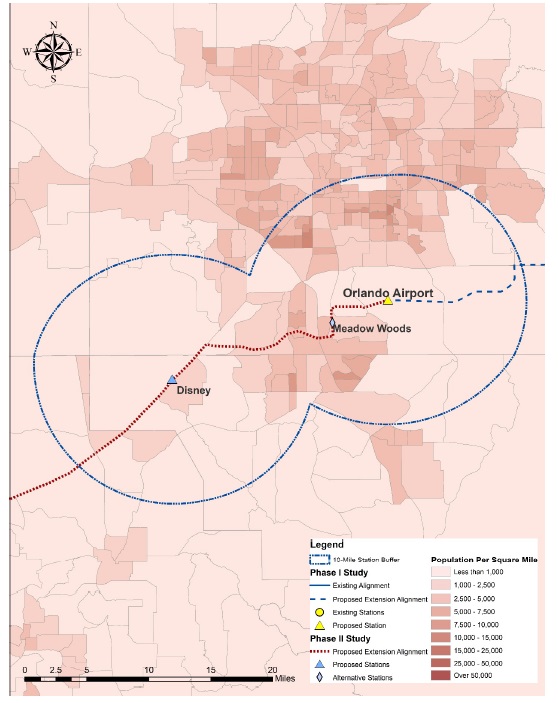

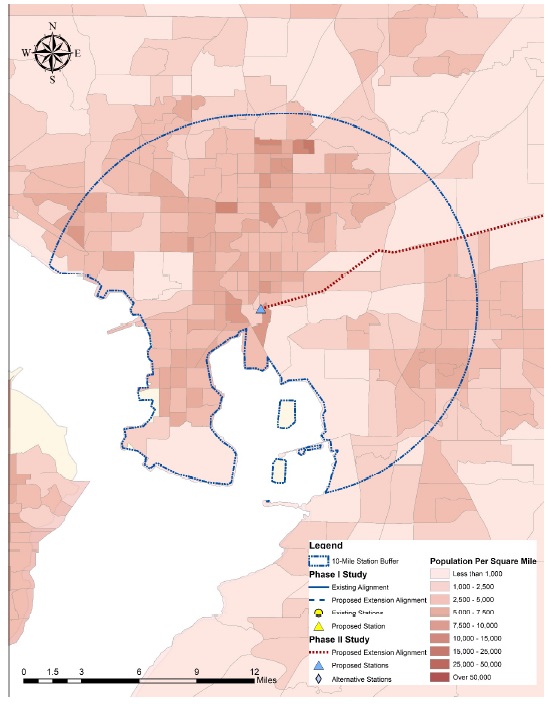

All Aboard Florida Operations, LLC commissioned Louis Berger U.S., Inc. (LB) to develop an investment grade ridership and revenue forecast study for the re-introduction of passenger rail service on its existing right of way. The proposed new passenger rail service, named Brightline, will be a privately owned and operated, intercity service connecting key cities in Southeast Florida with key cities in Central Florida and Tampa Area. This study was conducted in two distinct phases, the Phase I Study evaluated Brightline service between Southeast Florida and Orlando as indicated in Figure ES-1, while the Phase II Study evaluated the incremental ridership and revenue associated with an extension of service to Tampa with an intermediate stop at Disney World.

The objective of this study is to provide an independent overview of ridership and revenue that will inform and advance the project planning efforts and decisions of potential investors and funding partners.

| 7 | P a g e |

ES-1 Overview of the Investment Grade Study Process

The ridership and fare revenue forecasts presented in this report are characterized as being investment-grade in that they provide a level of information in data gathering and analysis that is typical of that required to support investment decision-making.1 The comprehensive nature of this study is underpinned by the following key features:

| ● | Independent approach by experienced travel demand forecasting consultants. |

| ● | Forecasting models constructed from the bottom up using data gathered from regional planning agencies, stakeholder organizations, and recognized commercial sources. |

| ● | Stated Preference Survey designed to measure characteristics of existing intercity travel demand. |

| ● | Pricing Research survey data to support findings on willingness to pay and induced demand |

| ● | A critical, benchmarked assessment of economic growth projections that are used to estimate the overall future growth in travel demand. |

| ● | The development of a forecasting models for Brightline based on current travel, transport system and economic growth data. |

| ● | Alternative model estimates (sensitivity testing) intended to quantify the impacts of different assumptions of key forecasting inputs on forecast results. |

| ● | Emphasis on near term forecasts—investment decision makers commonly place greater emphasis on the early years of operation than the later years (which include growth that is expected, but not certain, to occur). |

Outputs of the forecast that were used to determine the economic, financial, and business planning dimensions of the proposed investment include the following:

| ● | Overall ridership demand estimates |

| ● | Station-station segment ridership estimates |

| ● | Market share analysis |

| ● | Market breakdown by user type (business/non-business, etc.) and geography |

| ● | Ridership demand with respect to level of service |

| ● | User benefit metrics (values-of-time) |

Louis Berger segmented its technical approach and analysis into five distinct areas of study outlined below. Each of these study areas are discussed in greater detail within their respective chapters of this report.

| ● | Market assessment (Section 2, 3) |

| ● | Travel demand model development and calibration (Section 4) |

| ● | Ridership and revenue forecast (Section 5) |

| ● | Sensitivity testing (Section 6) |

1 The key features noted in this section are intended to produce reasonable and reliable forecast estimates. However, it is not possible to forecast future events with certainty. Assumptions regarding economic growth, competition between modes, and external factors affecting overall travel demand and Brightline usage may prove inaccurate. Changes from these assumptions could produce lower or higher ridership than the estimates contained in this report. Please see our disclaimer for more information.

| 8 | P a g e |

ES-2 Study Process

To determine the extent and magnitude of the demand for a new mode of travel between Central Florida, Tampa Area and Southeast Florida, Louis Berger undertook a thorough assessment of the existing and potential future intercity travel market, the attributes of the current modes of travel in the corridor, and prospects for future growth. The study included the following key activities.

| ● | Research to Establish Market Size and Catchment Area– Residents and visitors to cities in the corridor make hundreds of millions of trips per year, but only a select portion of these trips involve travel between the central business districts and surrounding activity centers that would be served by Brightline stations. To identify the addressable market, Louis Berger gathered extensive data on current levels of travel between the city pairs by mode, trip purpose, and time (time of day, day of week). Louis Berger used vendor-provided mobile phone data and findings from recent primary research on traveler preferences to determine the size of the market. The research established an addressable market of over 413 million intercity trips per year in areas reasonably served by the stations (see Section 3). These findings on the size and characteristics of the market are consistent with previous studies undertaken for rail projects in Florida, and provide a conservative base for the demand forecast. |

| ● | Identification of Travel Network and Competing Modes of Travel – The demand forecasting process also requires a thorough understanding of the travel network and the schedule, journey time, and cost attributes of all modes of travel using the network. This report outlines the assumptions and data sources Louis Berger used to establish the highway, rail, and air travel network. The report also documents the attributes of each mode of travel used as inputs to the demand forecast (see Section 4). |

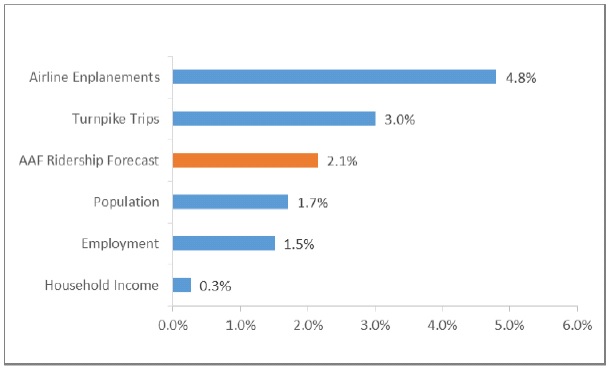

| ● | Assessment of the Prospect for Growth in Travel – An investment grade forecast requires thorough examination of the prospect for growth in the overall travel market. By gathering data from regional transportation planning agencies and other accepted public and commercial sources, Louis Berger established conservative and reasonable growth rates for the overall market based on observed trends in each segment. Based on observed trends in each of the metropolitan regions within the corridor, Louis Berger expects the overall number of long-distance intercity trips between Central and Southeast Florida to grow by 2.9 percent per year; and between Tampa Area and Southeast Florida to grow by 2.2 percent per year. Louis Berger expects the overall number of shorter-distance trips between the cities in Southeast Florida to grow by 1.2 percent per year and between Central Florida and Tampa Area to grow by 2.2 percent per year (see Section 3). |

| ● | Primary Research on Traveler Preferences and Willingness to Pay – When travelers choose to make a journey by auto or by rail they weigh the time and money cost of travel and make a choice based in part on their travel budget and willingness to pay. Travel behavior is also influenced by trip purpose (e.g., business, leisure, commute, airport access) and other factors such as party size and need for a vehicle at the destination. The Brightline system is an entirely new type of service for the region whose unique features can only be tested in hypothetical scenarios that place Brightline against other competing modes. The current state-of-the-practice uses mode choice Stated Preference survey (SP) as the basis for understanding how individuals (or groups of individuals) value individual attributes, such as access time, in-vehicle travel time, headways, and cost - of a transportation choice (see Section 4 for description of the survey, administration, and analysis). Louis Berger also reviewed findings from a recent Pricing |

| 9 | P a g e |

Research survey conducted by Integrated Insights to benchmark data on traveler trip purpose, travel frequency, and willingness to pay (see Section 5).

| ● | Demand Forecasting – The Louis Berger study team employed best practices in discrete choice analysis and network travel demand forecasting to determine diversions from existing modes of travel to Brightline and ridership volumes on the Brightline system by city-pair segment. SP survey responses were used to develop a statistical model of mode choice and estimates of the passenger rail market share and is the basis of the Brightline ridership forecast (see Section 4). |

| ● | Sensitivity Testing– The report provides the findings of sensitivity tests demonstrating the effect of changes in key forecast assumptions on ridership and revenue (see Section 6). These sensitivity tests are used to establish the stability of the forecast model and inform project planning. |

This study was carried out in the context of previous public and private sector sponsored rail implementation studies in Florida that attempted to better understand the potential of passenger rail to relieve congestion and promote mobility and economic development. Louis Berger evaluated the following studies and used them as benchmarking references for the findings in this analysis:

| ● | Florida Overland Express (FOX): Public-private partnership between FDOT and FOX for high speed rail connecting Tampa, Orlando, and Miami. The State withdrew support for the project, in 1999. |

| ● | Investment Grade Ridership Study for the Tampa-Orlando corridor: Performed in 2002 on behalf of the Florida High Speed Rail Authority. The Florida High Speed Rail Enterprise published a two-page update to that forecast in September 2009. |

| ● | In 2006, FDOT prepared the Florida Intercity Passenger Rail Vision Plan, a plan that builds upon previous studies exploring the potential of high speed rail to assist in meeting the State’s mobility needs. |

ES-3 Overview of the Brightline Rail Service

The Phase I of proposed Brightline service will provide new express passenger rail service connecting Orlando with three key urban areas in Southeast Florida – West Palm Beach, Fort Lauderdale, and Miami. The Phase II of proposed Brightline service will provide expanded service beyond Orlando to Lakeland and Tampa Area, with additional stops at Disney World and Meadow Woods. The Brightline service will be privately owned and operated by All Aboard Florida Operations, LLC and will primarily run along the existing transportation corridors including a rail corridor currently used for freight rail operations by Florida East Coast Railway, and an existing highway corridor being accessed in partnership with the State of Florida and other regional governmental entities. Brightline services are unique for Florida: no intercity rail alternative comparable to the proposed Brightline service exists currently. Special features include the following:

| ● | Travel time savings: Substantial time savings to current users of auto, bus, traditional rail and even air traveling between the city pairs |

| ● | Frequency: Consistent, hourly departures seven days per week to fit the schedules of both business and leisure travelers |

| ● | Booking: Online and mobile booking with reserved coach and business class seating for easy boarding |

| ● | Amenities: Free Wi-Fi, convenient outlets, comfortable seating, food and beverage service and related amenities on board |

| 10 | P a g e |

| ● | Stations: Modern, centrally located stations in Southeast Florida and Tampa Area cities, and an airport-based station in Orlando, with good intermodal connectivity (i.e. connections to Metrorail, Metromover, Tri-Rail – with direct connection to Miami International Airport – Broward County Transit, The WAVE Streetcar, and SunRail), parking and ridesharing services available |

In addition to the travel time savings offered by Brightline, the ease of travel and related amenities to the service described above are expected to draw a substantial amount of travelers who attribute a high value to comfort, productivity, and efficiency.

ES-4 Relevant Market for High Speed Rail

With a population of 6.01 million in 2015, the South Florida metropolitan area is the most populous metropolitan area in the Southeastern United States and the fourth most populous urbanized area in the United States. Main cities include Miami, Fort Lauderdale, Pompano Beach, West Palm Beach, and Boca Raton. Miami International Airport is the busiest airport in Florida (38.6 million passengers in 2015) and ranks second in the United States in terms of international passenger count, with 21.2 million international passengers annually. Central Florida’s main city, Orlando, and the surrounding Greater Orlando region attracted 68 million visitors in 2016. Attractions include Walt Disney World Resort, Universal Orlando Resort and SeaWorld Parks & Entertainment. Convention and trade show attendance at the Orange County Convention Center, in 2015 equaled 1.4 million. In addition, a record 22.6 million people visited Tampa Bay Area; Orlando and Miami are among top three visitor sources, leading a high demand for travelling between Central Florida and Tampa Area and between Southeast Florida and Tampa.

Orlando International Airport, a station location, is the second busiest airport in Florida after Miami International Airport with 41.9 million passengers in 2016. Orlando’s secondary airport, Orlando Sanford International Airport had 2.75 million passengers in 2016 while cruise traffic at Port Canaveral accounted for 3.9 million passengers. A total of 18.7 percent of overseas non-resident travelers enter the United States through one of the main South Florida and Central Florida airports: Miami International Airport (12.4 percent); Orlando International Airport (4.1 percent) and Fort Lauderdale International Airport (2.2 percent).

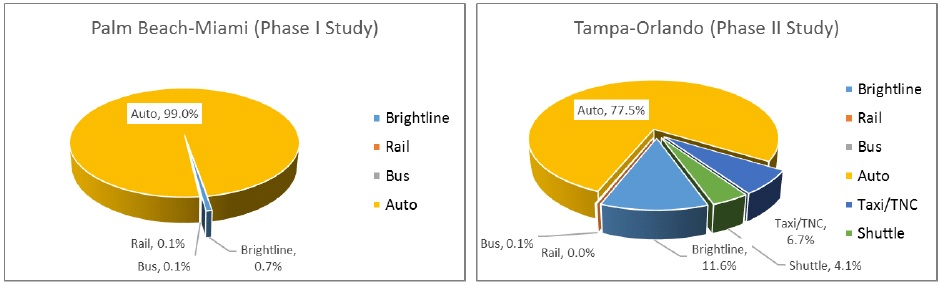

Auto vehicles are the dominant mode of intercity travel between Orlando and the Southeast Florida cities that Brightline will serve. The two main routes between the cities are the I-95 and the Florida Turnpike. Free-flow driving times between Miami and Orlando are estimated at approximately 4 hour 15 minutes along the I-95 and at 3 hour 50 minutes along the Florida Turnpike, which is a toll road. Travel times during congested peak periods can be substantially greater. Air, rail and bus account for a small proportion of trips between the Orlando and Miami; most passengers traveling by air on the more than thirty daily flights between Miami and Orlando are connecting to another destination. Two AMTRAK trains, the Silver Meteor and the Silver Star, each run once daily between Orlando and Southeast Florida. The Silver Meteor, which is the fastest because it does not make a detour to Tampa, takes about 3 hour 45 minutes from Orlando to West Palm Beach and 5 hours 35 minutes from Orlando to Miami. In addition, there are a few private bus companies that operate several buses daily between Orlando and Southeast Florida along the Florida Turnpike. Similarly, auto vehicles play a major role in intercity travel between Tampa Area and the Southeast Florida cities. The major route connecting these two areas is I-75, via which the free-flow driving time is

| 11 | P a g e |

estimated at approximately 4 hours. Air, rail and bus together only account for 10 percent of total trips between these two areas.

Travel between Central Florida and Tampa Area is almost exclusively by auto, accounting for 99 percent of total trips. The main alternative mode of travel is bus: private bus companies provide several daily commuting bus service connecting Orlando and Tampa, with travel time up to 70 minutes. Travel within Southeast Florida is also mostly by automobile. Between Miami and West Palm Beach the Florida Turnpike runs parallel with I-95. Driving from Miami to West Palm Beach takes about 1 hour 17 minutes on the I-95 and 1 hour 27 minutes on the Turnpike. Driving time between Miami and Fort Lauderdale is about 35 minutes while the drive from Fort Lauderdale to West Palm Beach takes about 50 minutes. During congested peak periods it is not uncommon for these travel times to increase by 30 to 50 percent due to incidents or weather making journey and arrival times during these key periods unreliable. The main alternative mode of transportation is rail. Tri Rail, a commuter rail line run by the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority (SFRTA) links Miami, Fort Lauderdale, and West Palm Beach. The 71-mile line has 18 stops and an annual ridership of 4.2 million.

According to the 2016 INRIX Global Traffic Scorecard, the Central and South Florida highways are the most congested in the State, which results in millions of hours of travel delay and excessive fuel consumption and pollutant emissions. Southeast Florida is ranked as the 10th most congested urban area globally in terms of peak hours spent in congestion and has the 5th worst traffic congestion in the United States2. State and local agencies have been active in evaluating alternatives to the severe congestion on north-south roadway links. In June 2010, FDOT prepared the I-95 Transportation Alternatives Study, in consultation with the Department of Law Enforcement, the Department of Environmental Protection, the Division of Emergency Management, the Office of Tourism, Trade and Economic Development and affected MPOs and regional planning councils located along the corridor. The study, which provides an assessment of concerns and proposed solutions related to I-95, found that “I-95 is overwhelmed with traffic demand” and that “[t]ravel within specific urban areas along the I-95 corridor is highly congested in peak travel periods due to single driver automobile use.” This study concluded, among other things, that “[p]assenger rail service presents a mobility option to serve Florida’s East Coast along the I-95 corridor” with multiple benefits including the reduction of “fossil fuel use and greenhouse gases (GHGs); job creation and economic development around station locations; and, better connectivity between northern and southern sections of Florida.”

The potential for intercity rail as a viable alternative has long been recognized by many, including FDOT, which developed the Florida Intercity Passenger Rail “Vision Plan” (FDOT, August 2006). Among other things, the plan found that the state’s intercity travel market would grow at an average annual rate of 3.5% from 2006 to 2040 (FDOT, August 2006). This increase will exacerbate existing transportation problems and require significant development of new infrastructure to meet the needs of this market. In June 2009, FDOT released the 2009 Florida Rail System Plan: Policy Element (FDOT, March 2009), which updated the 2006 Florida Freight and Passenger Rail Plan and built upon previous rail planning efforts, including the 2006 Florida Intercity Passenger Rail Vision Plan to show that:

| ● | There is a rising public interest in rail options to meet intercity and regional mobility needs; |

2http://inrix.com/press-releases/los-angeles-tops-inrix-global-congestion-ranking/

| 12 | P a g e |

| ● | The existing congestion on Florida’s highways may be mitigated by a passenger rail alternative, which would also serve to increase the mobility of tourists, business travelers, and citizens – especially older Floridians; and |

| ● | Reliance on alternate transit options is expected to increase in light of growing concerns over dependence on foreign oil, fluctuating gas prices, and fuel supply disruptions as a result of natural disasters. |

ES-5 Key Assumptions

In order to provide the level of information appropriate for evaluation by lenders and investors during the planning stage of project development, Louis Berger made several key assumptions for the Base Case Forecast, as follows:

| ● | The forecast study area is limited to the extent of the metropolitan areas in Central and Southeast Florida and Tampa Area. Station market catchment areas and trip filters were developed to establish reasonable boundaries for the addressable market and to eliminate illogical station access patterns. As described in Section 3, this is the basis for establishing the size of the candidate market at over 31 million trips per year for the long-distance journey between Orlando and the three cities in Southeast Florida and between Tampa Area and Southeast Florida. When trips between the three cities in Southeast Florida and trips between Tampa Area and Central Florida are considered along with long distance trips, the number grows to over 413 million. |

| ● | Base year trip tables used in the model were developed separately for each mode available between each city pair. As noted in Section 3.6, Louis Berger relied on mobile phone location data purchased from a third-party vendor to determine origin-destination patterns and the size of the automobile trip travel market, which is predominant in size within the addressable market geography. This data was calibrated to volumes on the Florida Turnpike and other intercity routes and verified through an econometric model that linked economic variables to traffic growth on the Florida Turnpike and other intercity routes (that basis of the data being a traffic station counter representative of the Central-Southeast Florida traffic). The data was further adjusted downward to capture captive auto users and lower visitation volumes. Trips tables for other modes of travel were based on information obtained from relevant planning agencies and operators. |

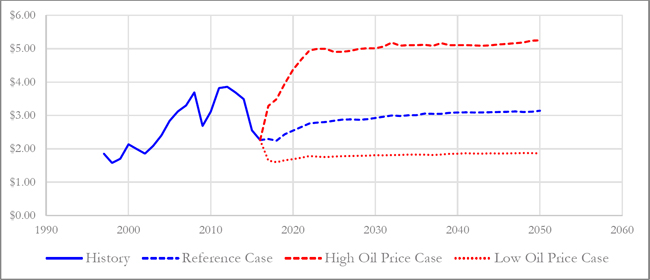

| ● | Brightline fares assumed in the modeling process were provided by All Aboard Florida Operations, LLC and validated by Louis Berger, as outlined in Section 5.2. All fares and competing mode costs were fixed in real terms. For purposes of estimating the future cost of auto travel, gas prices were set at future levels estimated by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) reference case forecasts referenced in Section 4.5. This report assumes that over the long term, motor fuel will remain in adequate supply and future increases in fuel price will align with the current outlook of these EIA forecasts. In addition, future changes in fares for Brightline, made during the course of operations or otherwise, that differ from those outlined in this Report, may result in levels of ridership and/or revenue that differ from the forecast estimates contained in this Report. Costs associated with competing modes of intercity travel or modes access/egress to Brightline stations different from those assumed in this Report may result in levels of ridership and/or revenue that differ from the forecast estimates contained in this Report. |

| 13 | P a g e |

| ● | The estimation of the future travel market does not include any changes in the location of households or employment related to transit-oriented development in the areas surrounding the stations. |

| ● | We assume that the trajectory of growth in trips will align with the information and estimates presented in Section 3. |

| ● | Congested auto travel times were accounted for in estimating station access and long-distance auto travel times, as summarized in Section 4.5. Given the history of growth in highway congestion and challenges in expanding the highway network, regional planners consider it likely that congestion within and between the regions will increase, making non-highway modes of travel more competitive. Changes in highway capacity or capacity or service levels associated with competing modes of intercity travel or modes access/egress to Brightline stations different from those assumed in this Report may result in levels of ridership and/or revenue that differ from the forecast estimates contained in this Report. |

| ● | Brightline presents users with a premium service unlike any other service in the State of Florida. It is often the case that Stated Preference surveys which underlie the mode choice model and forecast do not fully capture the value that users attribute to the premium nature of services such as Brightline. Our survey research and fare price benchmarking was designed to compensate for this providing the basis for a comprehensive view on traveler willingness to pay. |

| ● | Induced demand potential was based on a method of evaluating the improvement in the generalized cost of travel that has been accepted in other studies for high speed transportation in the U.S. As a novel form of transportation in Florida, Brightline is likely to experience ridership demand for tourism and leisure travel based on its convenience and amenities. |

| ● | This report assumes no major recession or significant economic restructuring will occur which could substantially reduce trip-making and traffic in the region. |

| ● | This report assumes no natural disasters will occur that could significantly alter travel patterns throughout the area served by Brightline. |

| ● | This report assumes no local, regional, or national emergency will arise which would abnormally restrict Brightline service, use of Brightline stations or connectivity to stations, or the use of motor vehicles, or other modes of travel, for station access and egress. |

Any significant departure from these basic assumptions could materially affect estimated Brightline ridership and revenue. Assumptions regarding economic growth, competition between modes and external factors affecting overall travel demand and Brightline usage are subject to uncertainty and may prove inaccurate. As noted herein, Louis Berger has relied on information developed by third parties regarding travel patterns and the outlook for economic conditions. Changes from these assumptions could produce lower or higher ridership than the estimates contained in this report. Please see our disclaimer for more information.

| 14 | P a g e |

ES-6 Key Findings and Ridership and Revenue Forecast

Our forecast evaluation revealed that introduction of Brightline service would complement existing modes of travel and draw a substantial number of business and non-business travelers. Station locations offered by Brightline in Miami, Ft. Lauderdale, West Palm Beach, Orlando (International Airport & Disney), and Tampa will provide an alternative source of transportation for travelers with origins or destinations at or near these urban cores. The thorough study effort resulted in the following key findings:

| ● | Substantial “Addressable Market” – Hundreds of millions of trips are taken annually between the four cities that will be served by Brightline. Louis Berger’s study included a determination of the portion of these total trips that both originate and terminate within a defined distance of a proposed Brightline station (a station “catchment area”). The Brightline addressable market is assumed to include only those trips beginning and ending within station catchment areas, as further defined in 2.10 of this report. Based upon detailed analysis, Louis Berger concluded that the addressable market for Brightline intercity service amounts to over 413 million trips made by individuals annually. |

| ● | Demonstrated Market Travel Growth – Intercity travel on the Florida Turnpike between Orlando and Miami grew by an average of 3.2 percent per year from 2001 to 2016. Average annual growth on I-95 from 2001 to 2015 was approximately 2.1 percent. |

| ● | Demonstrated Market Demographic Growth – In the past 30 years, population in the market area has grown by an annual average of 2.5 percent and employment has grown by an annual average of 3 percent. Within one mile of proposed Brightline stations, annual population growth has ranged from 2 percent to 5 percent since 1990 indicating strong growth in the urban core at the heart of the Brightline alignment. |

| ● | No Comparable Service – Brightline can provide travel time savings of 25% to 50% when compared to existing surface modes (auto, bus and rail) and with a journey time of around three hours from Orlando to Miami is competitive with air on door-to-door travel times. There is no comparable service to Brightline for intercity travel in the existing market. |

| ● | Established Willingness to Pay – The fares used in this study are backed up by two primary research efforts – a Stated Preference Survey and a Pricing Research Study commissioned by the project sponsor – which confirmed willingness to pay for the Brightline service at the price points utilized. Fares are highly competitive with existing modes of travel when time, tolls, and travel costs are considered and are comparable to other successful rail services in the U.S. |

| ● | Long-Standing Interest – Given the profile of the travel market and the central location of the rail line, there has been interest among stakeholders and the public in developing passenger service on the Florida East Coast corridor for decades. |

Estimated Ridership

Louis Berger prepared estimates for annual ridership and farebox revenue for both the short- and long-distance markets of the Brightline service. This forecast accounts for all elements important to future ridership potential including targeted market segments and induced ridership. Table ES-1 summarizes ridership and revenue for 2023, the first year stabilized ridership for the entire system is achieved.

| 15 | P a g e |

Table ES-1 Brightline Ridership and Revenue Forecast, 2023 (2016 $)

| Phase I Study (Miami-Orlando) | Phase II Study (Extension to Tampa) | Grand Total | |||||

| Short-Distance | Long-Distance | Subtotal | Short-Distance | Long-Distance | Subtotal | ||

| Ridership | 3,079,472 | 3,534,197 | 6,613,669 | 1,967,353 | 935,992 | 2,903,345 | 9,517,014 |

| Fare Revenue | $100,763,367 | $298,773,216 | $399,536,583 | $34,053,816 | $145,891,900 | $179,945,716 | $579,482,299 |

| (1) | Short-distance (Phase I Study): Miami-Ft. Lauderdale, Miami-West Palm Beach (WBP), Ft. Lauderdale – WPB |

| (2) | Long-distance (Phase I Study): Southeast Florida-Orlando |

| (3) | Short-distance (Phase II Study): Disney-Orlando Airport, Tampa-Orlando |

| (4) | Long-distance (Phase II Study): Southeast Florida -Tampa |

Ridership and revenue for the initial years of Brightline is expected to start at relatively low levels and grow to a stabilized volume after two years for each segment of operations that is introduced. The low initial levels represent the time it takes for ridership to build up to long-term forecast levels as travelers become acquainted with the new rail service and adjust their trip-making habits. During 2017, management has made substantial investment in marketing, pre-launch ticket sales, and corporate block sales prior to the commencement of full-scale revenue service between Miami and West Palm Beach in May 2018. Management also intends to implement reduced price fares during an introductory period following the beginning of revenue service for each segment (see discussion in Section 5.2). Given these plans, for the short-distance trips, Louis Berger assumed, therefore, 40 percent of forecasted volumes in 2018, and 80 percent forecasted volumes in 2019. For the long-distance trips, Louis Berger assumed a two calendar year ramp-up period: ridership volumes for 2021 are 40 percent of forecasted volumes and 80 percent of forecasted volumes in 2022. These ramp-up assumptions are appropriate to estimation of initial year ridership and revenue, and are consistent with previous rail service forecasts in Florida (see discussion in Section 5.1.1 – Ramp-Up). The forecasts include the assumption that long-distance revenue service will begin in first quarter of 2021. The full service will reach stabilized volumes by 2023. Ridership and revenue for the full forecast length is summarized in the two figures below. The values for 2018-2023 account for ramp-up reductions.

Figure ES-2 Brightline Annual Ridership Forecast, 2018-2040

Source: Louis Berger, 2017, 2018

| 16 | P a g e |

Figure ES-3 Brightline Fare Revenue Forecast, 2018-2040 (2016 $)

Source: Louis Berger, 2018, 2018

Estimated Market Share

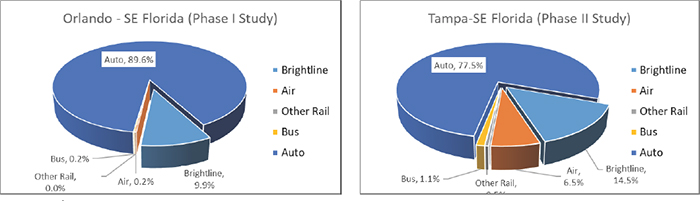

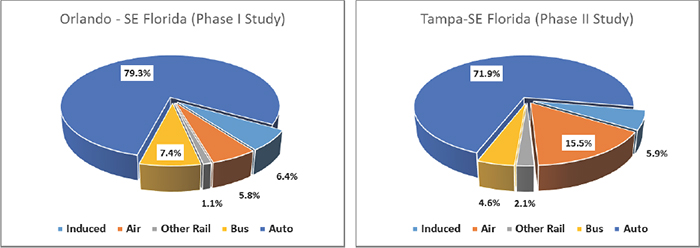

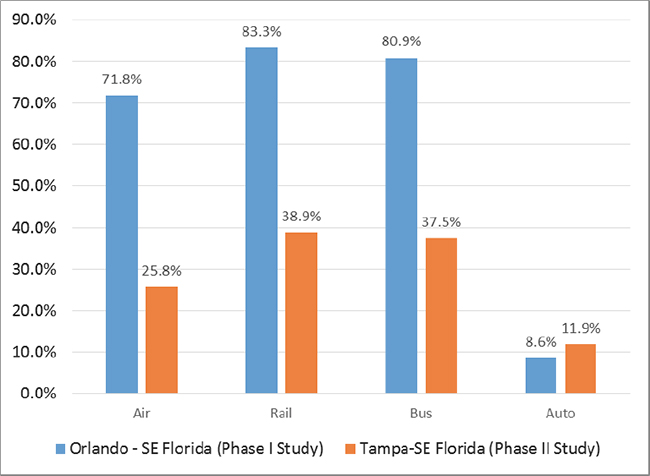

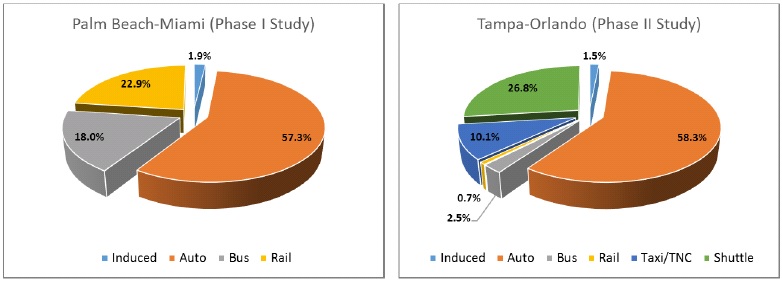

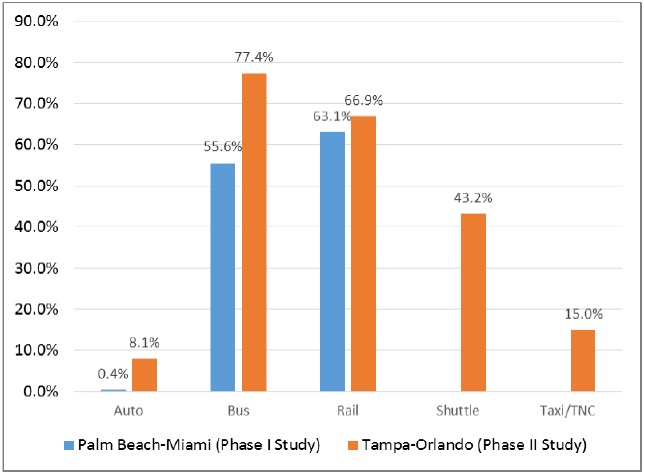

The forecast indicates that after the initial ramp up period, Brightline will serve approximately 10 percent of the overall market for travel between Southeast Florida and Orlando and approximately 15 percent of the market between Southeast Florida and Tampa. In the short-distance market, Brightline will serve approximately 0.74 percent of the overall market in Southeast Florida, and approximately 11 percent of the market between Tampa and Orlando (this includes the Disney to Orlando Airport travel market).

Figure ES-4 Brightline Long-Distance Market Share, 2023

Source: Louis Berger, 2017, 2018

| 17 | P a g e |

Figure ES-5 Brightline Short-Distance Market Share, 2023

Source: Louis Berger, 2017, 2018

Louis Berger conducted a series of sensitivity tests to evaluate the impact that changes in key input variables have on the ridership and revenue forecast. Table ES-2 presents the key assumptions that were altered and the corresponding impact on ridership and revenues for both the short- and long-distance market.

Table ES-2 Sensitivity Test Results, Ridership and Revenue % Change, 2023

| Sensitivity Test Assumption Modified | Change in Assumption | Phase I Study | Phase II Study | ||||||

| Short-Distance | Long-Distance | Short-Distance | Long-Distance | ||||||

| Ridership Effect | Revenue Effect | Ridership Effect | Revenue Effect | Ridership Effect | Revenue Effect | Ridership Effect | Revenue Effect | ||

| Brightline Travel Time | 10% decrease | 3.60% | 4.00% | 6.30% | 6.30% | 2.93% | 3.75% | 6.96% | 7.06% |

| 10% increase | -3.50% | -3.80% | -5.90% | -6.00% | -3.47% | -4.40% | -7.97% | -8.08% | |

| Brightline Frequency | 20% decrease | -3.70% | -3.90% | -1.50% | -1.60% | -6.26% | -5.41% | -1.82% | -1.83% |

| 20% increase | 3.80% | 4.00% | 1.50% | 1.60% | 3.89% | 3.36% | 1.11% | 1.11% | |

| Intercity Travel Time by Auto | 20% decrease | -10.40% | -10.90% | -11.20% | -11.40% | -10.95% | -13.01% | -11.95% | -11.86% |

| 20% increase | 11.90% | 12.60% | 12.60% | 12.70% | 12.19% | 14.99% | 13.28% | 13.16% | |

| Auto Fuel Prices* | Low: (-35% /-31%) | -3.30% | -3.50% | -3.10% | -3.10% | -1.72% | -2.90% | -2.29% | -2.30% |

| High: (+79% /+48%) | 7.90% | 8.40% | 7.40% | 7.50% | 2.81% | 4.75% | 3.67% | 3.68% | |

| Air Fares | 20% decrease | N/A | N/A | -0.30% | -0.30% | N/A | N/A | -1.94% | -2.12% |

| 20% increase | N/A | N/A | 0.10% | 0.10% | N/A | N/A | 1.67% | 1.85% | |

Source: Louis Berger, 2017, 2018

| 18 | P a g e |

| 1.0 | Introduction |

Each year, travelers make hundreds of millions of trips between the communities in Southeast and Central Florida and Tampa Area, making the region one of the most actively traveled areas in the United States. All Aboard Florida Operations, LLC initially commissioned Louis Berger U.S., Inc. (LB) to develop an investment grade ridership and revenue forecast study for the re-introduction of passenger rail service named Brightline.

An initial evaluation (hereafter referred to as the Phase I study) evaluated potential Brightline ridership demand associated with an alignment that connected through Miami, Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach in Southeast Florida, continued north along an existing rail right-of-way before turning west linking to the Orlando International Airport as shown in Figure 1-1. The initial Phase I Study investment grade analysis effort was conducted using a customized travel demand model based in part on Stated Preference survey research data collected in both Central and Southeast Florida in 2012 and was completed in December of 2017.

Brightline commenced passenger rail operations in Southeast Florida in January of 2018 and plans are currently underway to extend service to Orlando with a connection at the Intermodal facility at Orlando International Airport.

Figure 1-1 Proposed Route and Stations

Following the completion of the Phase I Study and the commencement revenue passenger service, Louis Berger was once again commissioned to evaluate the incremental ridership potential of extending service to Tampa with an intermediate stop at Disney World and the consideration of some potential alternative station locations along the

| 19 | P a g e |

Interstate 4 (I-4) corridor as also indicated in Figure 1-1.This follow up study (hereafter referred to as the Phase II Study) was conducted using a separate travel demand model based on primary market research data collected in 2018 that focused on both the Tampa-Orlando and Tampa/Lakeland-Southeast Florida travel corridors.

| 1.1 | Organization of Report |

Due to the differences in the travel demand models and the time frames of both the Phase I and Phase II Studies, this report presents elements of the analysis with appropriate distinctions of the two efforts. Furthermore, Louis Berger views the estimated Phase II Study ridership and revenue demand as incremental to the Phase I Study estimates.

| 20 | P a g e |

| 2.0 | Travel Market Socioeconomic and Demographic Conditions |

Despite the distances between city centers, the communities and economies of Southeast Florida, Central Florida, Lakeland and Tampa are interconnected in many ways. Substantial numbers of people travel between these areas for work, business, recreation, and other purposes. This section of the report describes the underlying socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the region as they pertain to the overall intercity travel market and an evaluation of prospects for growth. Figure 2-1 presents the travel market study area that is segmented into four regions:

| ● | Southeast Florida |

| ● | Central Florida (Orlando area) |

| ● | Lakeland (Polk County) |

| ● | Tampa |

Figure 2-1 Study Area

Source: Louis Berger. 2018

| 21 | P a g e |

| 2.1 | Population |

The study area consists of three major metropolitan regions with a total population of 11 million in 2017. Over 6 million people live in Southeast Florida, making it the seventh ranked urbanized area in the nation (behind New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas, Houston and Washington) and the most populous metropolitan area in the Southeastern U.S. The Tampa Area counted 2.7 million residents in 2017 and is the third ranked urbanized area in the Southeastern U.S. The Central Florida region counted 2.1 million residents in 2017, making it the fourth most populous metropolitan area in the Southeastern U.S. The Figure 2-2 presents the overview of population density in the study area. Figures of population density at a more granular level are included in Appendix A

Figure 2-2 Study Area Population Density

Source: Louis Berger, 2018

| 22 | P a g e |

The Central region experienced an average of 2.0 percent growth per year in the 2005-2015 period, 0.9 percent and 1 percent higher than the population growth rate of Southeast Florida and Tampa Area over the same period, respectively (Table 2-1).

Figure 2-3 POPULATION, 1975-2015 (IN THOUSANDS)

Source: Louis Berger, 2018 from data provided by Woods & Poole Economics, 2017

Table 2–1 Compound Annual Growth Rate in Population

|

Region/County/Area

|

1975-

2015 |

1995-

2015 |

2005-

2015 |

2010-

2015 |

|

Southeast Florida

|

1.9%

|

1.4%

|

1.1%

|

1.5%

|

|

West Palm Beach

|

2.0%

|

1.4%

|

0.8%

|

1.6%

|

|

Broward

|

1.5%

|

1.3%

|

1.2%

|

1.4%

|

|

Miami-Dade

|

2.8%

|

1.7%

|

1.1%

|

1.4%

|

|

Central Florida

|

3.1%

|

2.5%

|

2.0%

|

2.3%

|

|

Orange

|

2.8%

|

2.5%

|

2.0%

|

2.3%

|

|

Osceola

|

5.4%

|

4.3%

|

3.6%

|

3.7%

|

|

Seminole

|

3.0%

|

1.5%

|

1.0%

|

1.2%

|

|

Lakeland Area (Polk County)

|

2.1%

|

1.9%

|

1.7%

|

1.5%

|

|

Tampa Area

|

1.5%

|

1.2%

|

1.0%

|

1.3%

|

|

Hillsborough

|

2.1%

|

2.0%

|

1.7%

|

1.8%

|

|

Pinellas

|

0.9%

|

0.3%

|

0.2%

|

0.7%

|

|

Total Study Area

|

2.0%

|

1.6%

|

1.3%

|

1.6%

|

Source: Louis Berger, 2017 from data provided by Woods & Poole Economics, 2017

| 23 | P a g e |

Figure 2-4 COMPOUND ANNUAL GROWTH RATE IN POPULATION

Source: Louis Berger, 2018

Population growth in the study area as a whole has had an average annual gain of 2.0 percent since 1975 (see Table 2-1). In the past 20 years the growth rate has moderated to 1.6 percent.

| 2.2 | Population Forecasts |

In Southeast Florida, three MPO regularly update their long-range transportation plans for the three county urbanized areas. These plans include updates to the outlook on the socioeconomic factors that underpin travel demand. These plans include official forecasts for population through 2040 from a base year of 2010. In Central Florida, MetroPlan Orlando is the MPO for Orange County, Osceola County, and Seminole County. The MPO’s 2040 Long Range Transportation Plan includes population projections for 2040. Similarly, Polk County TPO provides population projections for 2040 for the county (Lakeland Area in this report); Hillsborough MPO along with Forward Pinellas (Pinellas’s MPO) and Sarasota/Manatee’s MPO provides population projections for 2040 for Tampa area. Figure 2-5 shows the levels and rates of growth expected by study areas.

| 24 | P a g e |

Figure 2-5 MPO POPULATION FORECAST BY COUNTY, 2010-2040 (IN THOUSANDS)

Source: Louis Berger, 2018 from MPOs’ 2040 Long Range Transportation Plan. Central Florida is composed of Orange, Osceola, and Seminole counties. Southeast Florida is composed of Palm Beach, Broward, Miami-Dade Counties; Lakeland Area is composed of Polk County; Tampa Area is composed of Hillsborough, Pinellas and Manatee Counties.

The Southeast Florida forecast calls for the region to experience more moderate levels of increase than in the past, growing at an average annual rate of 0.8 percent from the 2010 Census population count. Regional population is expected to reach 7.0 million in 2040, with over 3.3 million residents in Miami-Dade. The Central Florida MPO forecasts growth at an annual average rate of 1.4 percent from the 2010 Census Population count, reaching 2.8 million residents in the MPO by 2040. The Lakeland area MPO (Polk County MPO) forecasts growth at an annual average rate of 1.8 percent from the 2010 Census Population count, reaching 0.9 million residents in the area by 2040; The Tampa area MPOs forecast growth at an annual average rate of 0.9 percent from the 2010 Census Population count, reaching 2.8 million residents in the area by 2040.

In accounting for future growth in intercity trips, Louis Berger utilized the established travel demand forecasts of the MPOs. To ensure that these forecasts represent reasonable levels of growth when compared to more recent projections, Louis Berger undertook a review of alternative population forecast sources.

Two alternative sources were available at the county level. The Bureau of Economic and Business Research (BEBR) at the University of Florida produces population projections based on forecasts of natural increase and net migration flows. These projections are updated annually and include three different levels-low, medium and high.

Louis Berger also obtained projections developed by Woods & Poole Economics, Inc., a private consulting firm that maintains and annually updates county-level projections for the U.S. (CEDDS - Complete Economic and Demographic Data Source, 2017). With its detail and frequent updates, this source is often used for comparison with official estimates in demand forecasts and due diligence studies.

| 25 | P a g e |

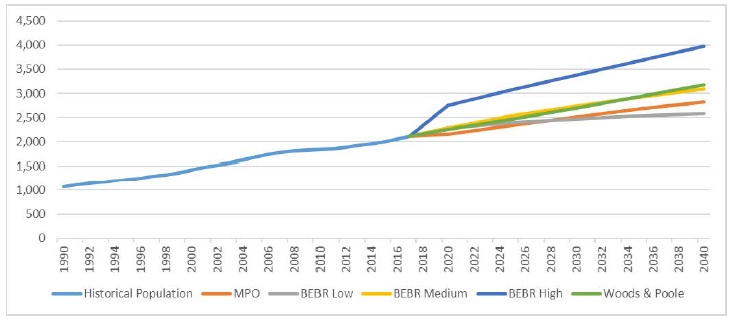

Figure 2-6 SOUTHEAST FLORIDA POPULATION FORECAST

Source: Louis Berger, 2018

Figure 2-7 CENTRAL FLORIDA POPULATION FORECAST

Source: Louis Berger, 2018

| 26 | P a g e |

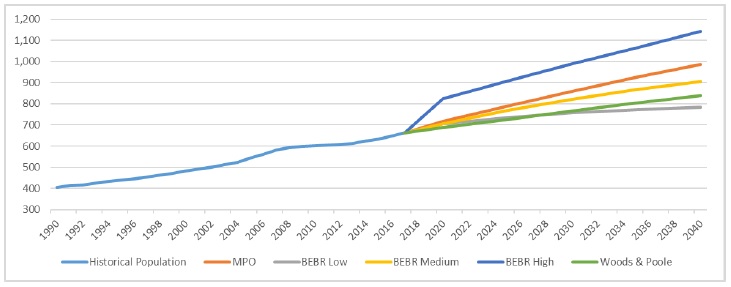

Figure 2-8 LAKELAND POPULATION FORECAST

Source: Louis Berger, 2018

Figure 2-9 LAKELAND POPULATION FORECAST

Source: Louis Berger, 2018

For the whole study area, BEBR “Low” case is projecting the slowest rate of growth for the region overall; The overall population level in 2040 projected by BEBR “Medium” is 6 percent higher than the MPO forecast. It is important to note that the MPO forecasts for all study areas between the “low” and “medium” case projections provided by BEBR. Woods and Poole see higher prospects for growth for the region in general than the BEBR “Low” and “Medium” case and the MPO forecasts but lower than the BEBR “high” case projection as shown in the Figure 2-6, 2-7, 2-8, and 2-9.

| 27 | P a g e |

| 2.3 | Employment |

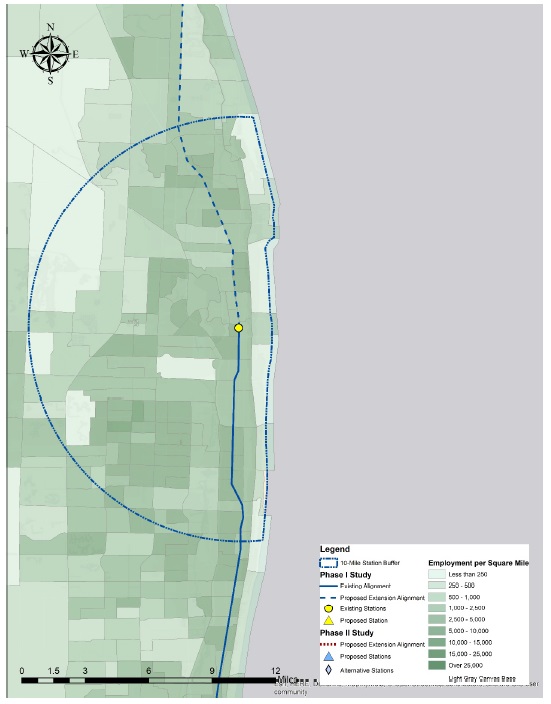

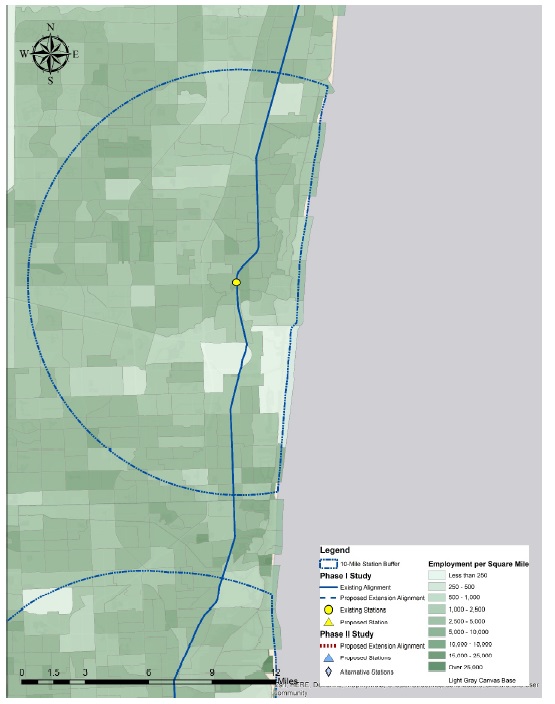

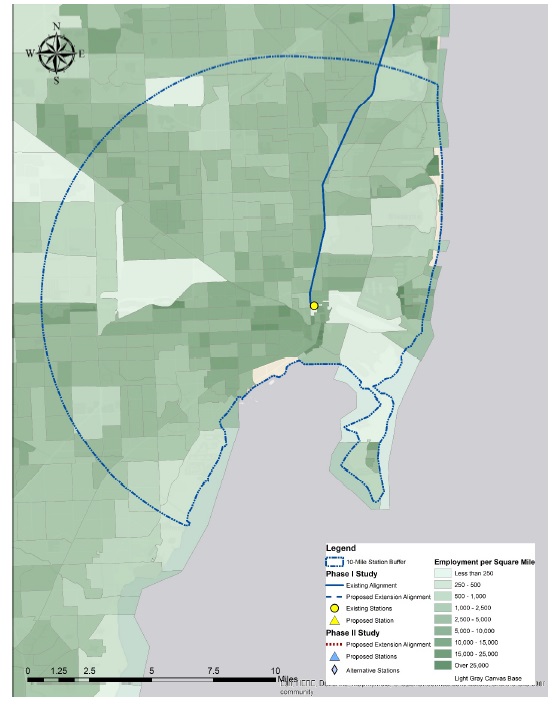

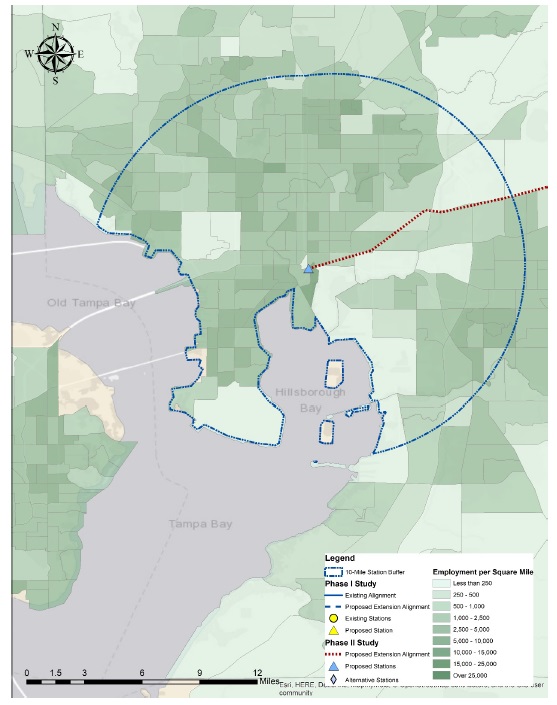

The study area contains more than two-third of all employment in the state of Florida. The Southeast Florida region in particular is a major employment center in Florida, comprising one third of the state’s total employment base. Over 6.9 million people worked in the study area in 2015. Figure 2-10 depicts the employment density of study area. Figures of employment density at a more granular level were included in the Appendix B.

Figure 2-10 Study Area Employment Density

Source: Louis Berger, 2018

| 28 | P a g e |

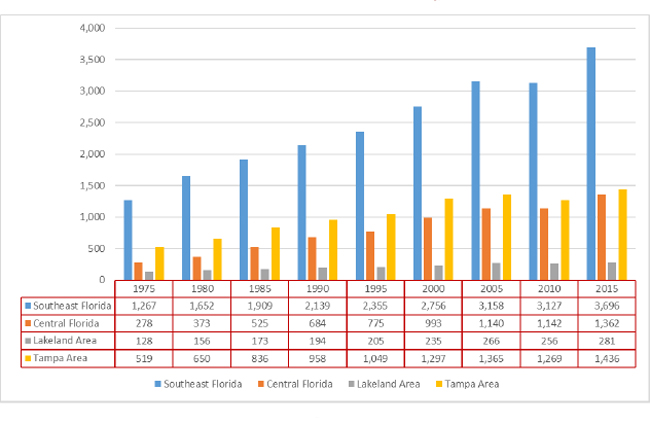

There was a slight dip in employment between 2005 and 2010 due to the recession and credit crisis; however, employment levels appear to have recovered. The Southeast Florida region has experienced substantial growth since 1975 when it had 1.27 million jobs. Employment in Central Florida totaled almost 1.4 million in 2015, up from 278,000 jobs in 1975. Employment in Tampa area totaled more than 1.4 million in 2015, up from 519,000 jobs in 1975 (Figure 2-11).

Source: Louis Berger, 2018 from data provided by Woods & Poole Economics, 2017

| Region/County/Area | 1975- | 1995- | 2005- | 2010- |

| 2015 | 2015 | 2015 | 2015 | |

| Southeast Florida | 2.7% | 2.3% | 1.6% | 3.4% |

| Palm Beach | 3.7% | 2.7% | 1.3% | 3.6% |

| Broward | 3.2% | 2.2% | 1.3% | 3.1% |

| Miami-Dade | 2.1% | 2.1% | 1.9% | 3.5% |

| Central Florida | 4.1% | 2.9% | 1.8% | 3.6% |

| Orange | 3.8% | 2.7% | 1.9% | 3.7% |

| Osceola | 5.7% | 4.2% | 2.7% | 4.5% |

| Seminole | 4.8% | 2.8% | 0.8% | 2.6% |

| Lakeland Area (Polk County) | 2.0% | 1.6% | 0.5% | 1.9% |

| Tampa Area | 2.6% | 1.6% | 0.5% | 2.5% |

| Hillsborough | 2.9% | 2.0% | 0.9% | 3.1% |

| Pinellas | 2.2% | 1.0% | -0.1% | 1.7% |

| Total Study Area | 2.9% | 2.2% | 1.3% | 3.2% |

| Source: Louis Berger, 2018 from data provided by Woods & Poole Economics, 2017 |

| 29 | P a g e |

Employment growth in the region as a whole has averaged an annual gain of 2.9 percent since 1975 (see Table 2-3). In the past 20 years the growth rate has moderated to 2.2 percent. With the effects of a major recession still being felt, growth since 2005 has averaged 1.3 percent.

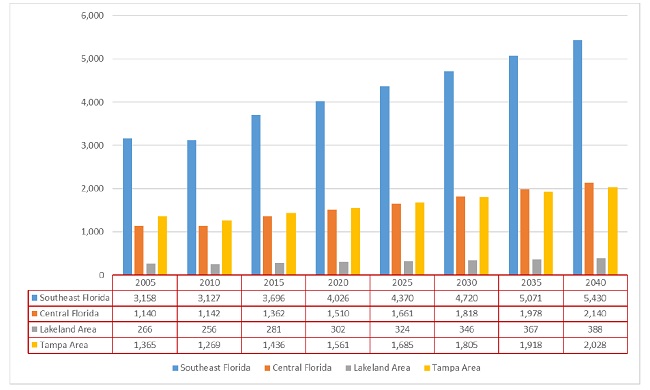

| 2.4 | Employment Forecasts |

In Southeast Florida, regional employment is expected to reach 5.4 million in 2040. In Central Florida, employment is expected to grow at 2.1 percent annually, reaching 2.1 million jobs in 2040. In Tampa area, employment is expected to grow at 1.4 percent annually, reaching 2 million jobs (Figure 2-12).

Source: Louis Berger, 2017 from data provided by Woods & Poole Economics, 2017

To ensure that these forecasts represent reasonable levels of growth when compared to more recent projections, Louis Berger undertook a review of alternative employment forecast sources other than Woods & Poole.

The other source involved employment projections was developed by MPOs’ Long Range Transportation Plan. These forecast include projections for 2040. MPO forecasts see higher prospects for growth for the region in general

| 30 | P a g e |

| 2010 | 2040 | CAGR | ||||

| County | MPO | Woods&Poole | MPO | Woods&Poole | MPO | Woods&Poole |

| Southeast Florida | 2,717 | 3,127 | 3,681 | 5,430 | 1.0% | 1.9% |

| Palm Beach | 571 | 735 | 820 | 1,362 | 1.2% | 2.1% |

| Broward | 730 | 977 | 806 | 1,649 | 0.3% | 1.8% |

| Miami-Dade | 1,416 | 1,415 | 2,055 | 2,419 | 1.2% | 1.8% |

| Central Florida | 1,128 | 1,142 | 1,679 | 2,140 | 1.3% | 2.1% |

| Orange | 814 | 823 | 1,174 | 1,511 | 1.2% | 2.0% |

| Osceola | 88 | 101 | 140 | 231 | 1.5% | 2.8% |

| Seminole | 225 | 217 | 366 | 397 | 1.6% | 2.0% |

| Lakeland Area (Polk County) | 243 | 256 | 436 | 388 | 2.0% | 1.4% |

| Tampa Area | 1,228 | 1,269 | 1,678 | 2,028 | 1.0% | 1.6% |

| Hillsborough | 711 | 752 | 1,112 | 1,303 | 1.5% | 1.8% |

| Pinellas | 517 | 516 | 566 | 725 | 0.3% | 1.1% |

| Total Study Area | 5,317 | 5,793 | 7,474 | 9,987 | 1.1% | 1.8% |

With no Census 100% Count available for employment, variations in long-term employment forecasts and base year measurements are not uncommon, especially during periods of volatility in economic conditions.

| 2.5 | Income |

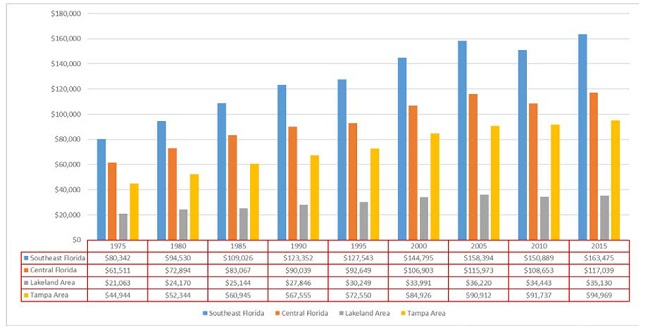

Total personal income in the study area was over $400 billion (2017 dollars) in the year 2015. Per Capita personal income increased by 1.7 percent on average annually in the study area between 1975 and 2015. In particular, Southeast Florida had the largest gains in per capita personal income over this period with average annual increases of 1.8 percent between 1975 and 2015; Central Florida had per capita personal income gains of 1.6 percent on average annually during the 40 year period from 1975 to 2015; Tampa area had per capita personal income gains of 1.9 percent on average annually during this 40 years period. However, there were negative per capita personal income changes between 2005 and 2015, which is likely due to the economic downturn which occurred during this time (Figure 2-13, Table 2-5).

| 31 | P a g e |

| Region/County/Area | 1975- | 1995- | 2005- | 2010- |

| 2015 | 2015 | 2015 | 2015 | |

| Southeast Florida | 1.8% | 1.2% | 0.3% | 1.6% |

| Palm Beach | 2.4% | 1.4% | 0.4% | 2.8% |

| Broward | 1.4% | 0.8% | -0.1% | 0.5% |

| Miami-Dade | 1.3% | 1.4% | 0.6% | 1.0% |

| Central Florida | 1.6% | 1.2% | 0.1% | 1.5% |

| Orange | 1.6% | 1.4% | 0.6% | 1.7% |

| Osceola | 1.2% | 1.1% | 0.1% | 1.1% |

| Seminole | 2.0% | 1.0% | -0.3% | 1.6% |

| Lakeland Area (Polk County) | 1.3% | 0.8% | -0.3% | 0.4% |

| Tampa Area | 1.9% | 1.4% | 0.4% | 0.7% |

| Hillsborough | 2.0% | 1.5% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| Pinellas | 1.8% | 1.3% | 0.5% | 1.0% |

| Total Study Area Average | 1.8% | 1.1% | -0.6% | 1.1% |

Source: Louis Berger, 2018 from data provided by Woods & Poole Economics, 2017

| 2.6 | Travel and Tourism |

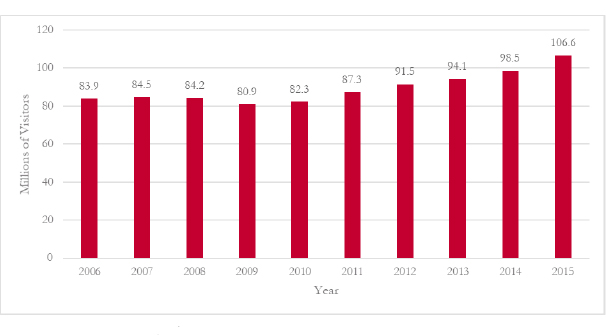

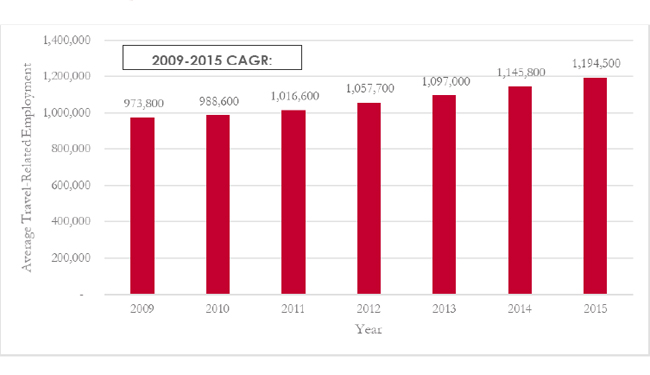

Given that the Central and Southern Florida regions and Tampa area are very popular tourism and business travel destinations, a good understanding of this travel market is essential. Louis Berger analyzed data from Visit Florida, the official tourism marketing corporation for the state of Florida. Visitation has been growing in this region in the past years. According to the latest data from Visit Florida, the state welcomed 106.6 million overnight visitors in 2015, an 8 percent increase from the prior year. Figure 2-15 below shows historical visitation to the state from 2006 through 2015. In addition, travel related spending supported a 4 percent increase in travel related employment between 2014 and 2015. Figure 2-16 below shows travel related employment between 2009 and 2015.

Source: Louis Berger, 2018 with data provided by Visit Florida, 2015

| 32 | P a g e |

Figure 2-15 TRAVEL RELATED EMPLOYMENT IN FLORIDA

Source: Louis Berger, 2018 with data provided by Visit Florida, 2015

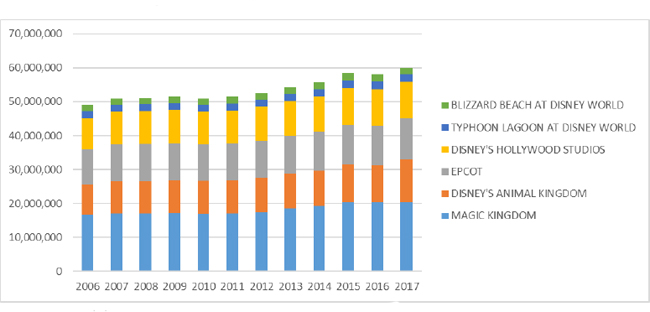

Among these visitations, Walt Disney World Resort (Disney) attracts a large portion of visitors each year. The proposed Brightline considers a stop near Disney. Louis Berger team analyzed current travel market data for Disney. Disney consists of six theme parks including: Magic Kingdom, Disney’s Animal Kingdom, Epcot, Disney’s Hollywood Studios, Typhoon Lagoon, and Blizzard Beach. Among these theme parks, Magic Kingdom has the highest number of visitors. Louis Berger team collected historical and current data from the Themed Entertainment Association (TEA) for theme part visitation as shown in below. The Figure 2-17 depicts strong growth of visitation to Disney, despite some decrease due to impact of the recession in 2008.

Figure 2-16 ANNUAL VISITATION BY THEME PARK

Source: 2017 Theme Index & Museum Index, Themed Entertainment Association, 2017

| 33 | P a g e |

|

|

2.7 | Domestic Visitation |

Of all the domestic visitors to the state of Florida in 2015, 89 percent traveled to the state for leisure activities, mostly during the spring and summer months. Domestic business travelers primarily visited central Florida (41%) followed by southeastern Florida (20%). Table 2-6 below details the main purpose of visitors’ trips by type of trip.

| Trip Purpose | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | ‘15/’14 % |

| Change | ||||

| LEISURE | 89% | 90% | 89% | -1 |

| General Vacation | 38% | 40% | 37% | -3 |

| Visit Friends/Relatives | 26% | 25% | 25% | 0 |

| Getaway Weekend | 10% | 11% | 13% | 2 |

| Special Event | 8% | 8% | 7% | -1 |

| Other Leisure/Personal | 7% | 6% | 8% | 2 |

| BUSINESS | 11% | 10% | 11% | 1 |

| Transient Business | 5% | 4% | 4% | 0 |

| Convention | 2% | 2% | 2% | 0 |

| Seminar/Training | 2% | 2% | 2% | 0 |

| Other Group Meetings | 2% | 1% | 2% | 1 |

Source: Louis Berger, 2018 with data provided by Visit Florida, 2015

The states of Georgia, New York, and Texas provided the largest number of domestic visitors to Florida in 2015. The average age of domestic leisure visitors to Florida in 2015 was 47.9. The largest percentage (30%) of visitors to Florida were age 35 to 49 followed by those age 18 to 34 (26%) (Profile of Domestic Visitors, Visit Florida 2015).

| 2.8 | International Visitation |

International visitors to Florida in 2015 were primarily travelling to the state on vacation or holiday (74%), staying for an average of 11 nights, similar to length of stay in 2014 (10.7). These visitors primarily visited the southeastern (68%) portion of the state. Trip purpose for visitors is detailed in Table 2-7.

| Main Trip Purpose | 2014 | 2015 |

| Vacation/Holiday | 74% | 74% |

| Visit Friends/Relatives | 12% | 12% |

| Business | 6% | 7% |

| Conference/Convention/Trade Show | 5% | 5% |

| Other | 3% | 3% |

Source: Louis Berger, 2018 with data provided by Visit Florida, 2015

The top market for international visitors is Canada with 3.8 million Canadians visiting Florida in 2015. These visitors stayed an average of 23 nights when visiting, up slightly from 22.7 nights in 2014. Most of these visitors traveled to southeastern (44%), central-central eastern (37%) or central west-southwestern (28%) Florida. Most of these visitors travelled to Florida via plane (52%) while over one third made the trip by car (36%). Few visitors traveled with children in 2015 (19%); many traveled alone (47%), and about 56% traveled with a spouse /partner or family /

| 34 | P a g e |

relatives. Most (76%) of these travelers stayed in a hotel or motel during their stay in Florida (International Visitors to Florida, Visit Florida 2015).

Despite the distances between city centers, the communities and economies of Southeast Florida, Central Florid, Lakeland, and Tampa Area are interconnected in many ways. Substantial numbers of people travel between these areas for business, journey to work, recreation, and other purposes. This section outlines the characteristics of the overall intercity travel market and an evaluation of prospects for growth. As shown in the Figure 2-1, the study area consists of Southeast Florida which incorporates Miami Urbanized Area, Central Florida which incorporates Orlando Urbanized Area, Lakeland which incorporates Lakeland Urbanized Area, and Tampa which incorporates Tampa Urbanized Area.

| 35 | P a g e |

| 3.0 | Intercity Travel Market for Brightline |

One of the key inputs to the mode choice model used to develop the Brightline ridership and revenue forecast is the size of the total addressable market for the proposed service. The total addressable market has the following characteristics:

| ● | Considers all travels within the addressable geographical market that can be logically served by the proposed Brightline long- and short- distance service. |

| ● | Includes all existing modes of travel (i.e. auto, rail, bus, ride share, air) |

| ● | Includes all market segments (visitors, residents) and trip purposes (airport-access trips, non-airport-access trips) |

This section provides a description of the existing modes of travel between the city pairs for long- and short-distance trips as well as an account of mode-specific historical, current, and future market sizes. The existing market size estimates for each mode form the basis of the trip tables for the base year, while future sizing is based on the estimated annual growth rates.

| 36 | P a g e |

| 3.1 | Addressable Market Geography for Brightline |

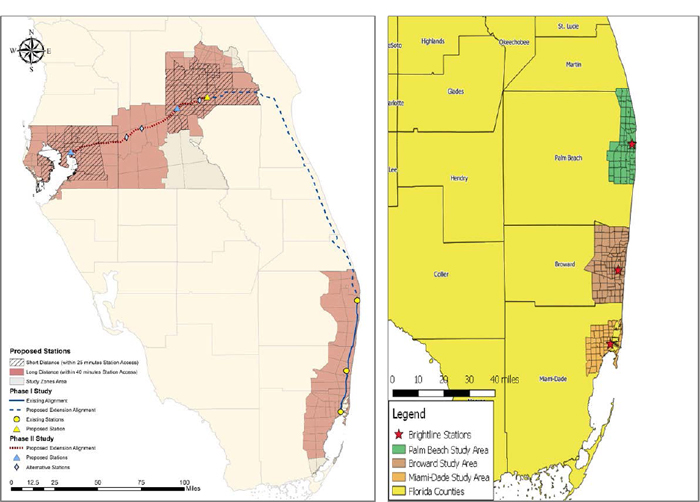

The earlier sections provided an overview of the regional socioeconomics in South and Central Florida and Tampa area. Following a review of the region, Louis Berger proceeded to identify the addressable market geography, or study area, for the Brightline service. This geography was determined based on the existing and proposed station locations as shown in Figure 1-1. The catchment area for long-distance intercity travel between Southeast Florida and Central Florida, between Southeast Florida and Lakeland and between Southeast Florida and Tampa was set to encompass an area within 30 to 40 minutes of driving time of a Brightline station. The catchment areas for shorter distance trips between Central Florida, Lakeland and Tampa area was set to encompass and areas within 20 to 30 minutes of drive time to the stations.

Source: Louis Berger, 2018

| 37 | P a g e |

Based on the station access travel times presented in Figure 3-1, Louis Berger developed study areas for both long and short distance market segments in the Phase I and Phase II Studies (Figure 3-2). The shaded portion of the left side depicts 40 minute drive time to Brightline stations that defined the catchment areas of both Phase I and II long distance market areas. The cross hatched portion of the same figure depicts the 25 minute drive time to stations in the Tampa-Orlando corridor that was used to define the Phase II Study catchment area for short distance trips. The right portion of Figure 3-2 depicts the short distance travel market catchment areas for the Phase II Study that was drawn based on the regional travel demand models zonal structure to delineate 20 minute station access times.

| 3.2 | Travel Market for Brightline Phase I Study |

The Brighline Phase I provides service connecting between Central and Southeast Florida (long-distance trips) and connecting cities within Southeast Florida (short-distance trips), where travel currently takes place by bus, rail (Amtrak and Tri-tail), air and car.

| 3.2.1 | Bus |

Travel by bus is available for both short- and long-distance trips. Intercity buses take approximately 4-6 hours to travel between Central and Southeast Florida and make stops in all three Southeast Florida cities. Intercity buses also serve all city pairs in Southeast Florida, and a popular set of transit bus routes connects Miami with Fort Lauderdale via the I-95 Express Lanes.

| 38 | P a g e |

Historical and Current Market Size

The intercity bus operators serving the Central-Southeast Florida market include Florida Express, Greyhound, Florida Sunshine, Red Coach, Megabus, Jet Set Express, Smart Shuttle Line, SuperTours, and Javax. Louis Berger estimated an average of 35 daily departures per direction between Central and Southeast Florida in 2017 based on published bus schedules of all the operators listed above. Assuming an average of 20 passengers per vehicle and an O-D distribution pattern similar to that of the rail travel market, Louis Berger estimated the 2016 daily volumes presented in Table 3-1.

Table 3-1 Estimated Daily Intercity Long-Distance Bus Person Trips

| City Pair | 2010 | 2016 | 2010-2016 CAGR |

| Orlando to Miami | 212 | 297 | +5.8% |

| Orlando to Fort Lauderdale | 126 | 193 | +7.4% |

| Orlando to West Palm Beach | 145 | 209 | +6.3% |

| Total | 483 | 700 | +6.4% |

| Source: Louis Berger, 2017 |

The number of intercity bus connections in Southeast Florida is limited to one public agency and a small number of privately operated services, which make local stops in the three Southeast Florida cities on the way to further destinations, primarily Orlando and Tampa. Broward County Transit (BCT) operates the 95Express and 595Express services. Each offer approximately 30 buses per day per direction and attract a total of approximate 1,650 riders per day (average annual daily basis from BCT reports). The full one-way fare is $2.65. This service is growing rapidly – as of 2014, the service carried only approximately 1,000 riders per day (average annual daily basis from BCT reports). Services on private operators cost in the $10-$25 range for a one-way trip between Southeast Florida cities. Greyhound offers about 13 daily trips from Miami to Fort Lauderdale and six from Miami through to West Palm Beach. Other intercity bus operators serving the Southeast Florida market include Florida Express, Florida Sunshine, Red Coach, and Megabus.

Bus ridership estimates in Southeast Florida were developed by assuming 30 riders per bus within the short-distance market (with 27 bus departures per day serving this corridor) and an O-D distribution pattern similar to the commuter rail market within the same corridor. Published ridership estimates obtained from Broward County Transit were also added to the initially estimated volume of bus trips within the Fort Lauderdale-Miami city pair. Table 3-2 shows the number of bus riders assumed for the base year forecast.

Table 3-2 Estimated Daily Short-Distance Bus Person Trips

| City Pair | 2016 |

| W. Palm Beach – Fort Lauderdale | 277 |

| W. Palm Beach – Miami | 184 |

| Fort Lauderdale – Miami | 2,006 |

| Total | 2,468 |

| Source: Louis Berger, 2017 |

| 39 | P a g e |

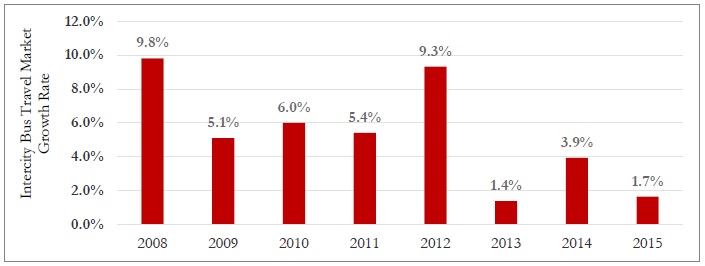

Growth Forecast

Future-year bus ridership volumes were estimated by applying growth rates obtained from the Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development at DePaul University, which monitors intercity bus travel patterns in the country.3 The initial surge in intercity bus travel growth observed since 2007 has slowed in recent years – as shown in Figure 3-3. As such, Louis Berger applied a 1.7% CAGR to estimate future-year bus ridership, as shown in Table 3-3 and Table 3-4.

Figure 3-3 Historical Growth in Intercity Bus Travel in the United States

Source: Louis Berger analysis of data from the Chaddick Institute, 2016

Table 3-3 Projected Daily Intercity Long-Distance Bus Person Trips

| City Pair | 2016 | 2040 | 2016-2045 CAGR |

| Central Florida to Miami | 297 | 478 | |

| Central Florida to Fort Lauderdale | 193 | 311 | |

| Central Florida to West Palm Beach | 209 | 337 | |

| Total | 700 | 1,125 | +1.7% |

| Source: Louis Berger, 2017 |

Table 3-4 Projected Daily Short-Distance Bus Person Trips

| City Pair | 2016 | 2045 |

2016-2045 CAGR |

| W. Palm Beach to Fort Lauderdale | 277 | 446 | |

| W. Palm Beach to Miami | 184 | 296 | |

| Fort Lauderdale to Miami | 2,006 | 3,225 | |

| Total | 2,468 | 3,967 | +1.7% |

| Source: Louis Berger, 2017 |

3 “The Remaking of the Motor Coach: 2015 Year in Review of Intercity Bus Service in the United States”, Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development at DePaul University, January 2016, https://las.depaul.edu/centers-and-institutes/chaddick-institute-for-metropolitan-development/research-and-publications/Documents/2015%20Year%20in%20Review%20of%20Intercity%20Bus%20Service%20in%20the%20Unite d%20States.pdf

| 40 | P a g e |

3.2.2 Long-Distance Rail (Amtrak)

The rail travel market analyzed in this study is separated into long- and short-distance markets. Amtrak provides services for the long-distance market, from Miami to Orlando twice a day. The Amtrak service makes 11 stops between Miami and Orlando, including Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach. In Miami, the Amtrak station is in Hialeah, approximately a 20-minute drive northwest of downtown. In Fort Lauderdale, the Amtrak station is on the west side of I-95, approximately a 10-minute drive west of downtown. In West Palm Beach, the Amtrak station is a short walk from the proposed Brightline station. In Orlando, the Amtrak station is downtown, approximately a 25-minute drive northwest from the airport.

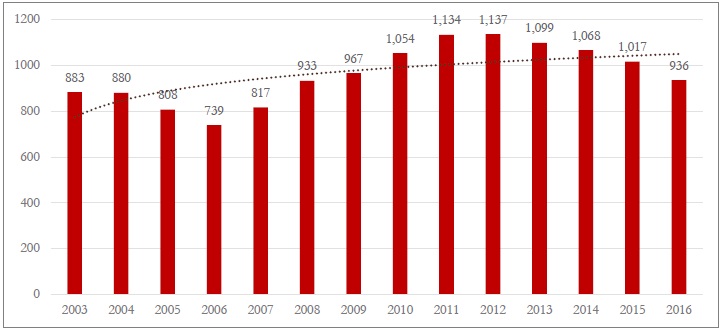

Historical and Current Market Size

Boarding and alighting data for all Amtrak stations in Florida is presented in Figure 3-4, showing ridership to, within, and from the state fluctuating between 700,000 and 1.25 million trips annually. The fluctuations around an overarching trend of growth between 2003 and 2016 reflect shifts in economic conditions as well as competitive dynamics overall in the intercity travel market (fuel prices, growth in intercity bus travel, etc.).

Figure 3-4 Amtrak Florida Station Boardings

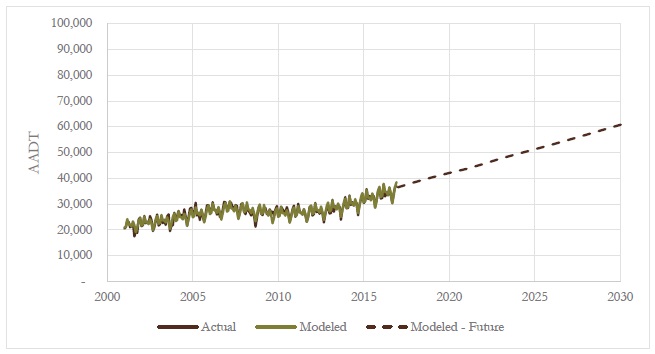

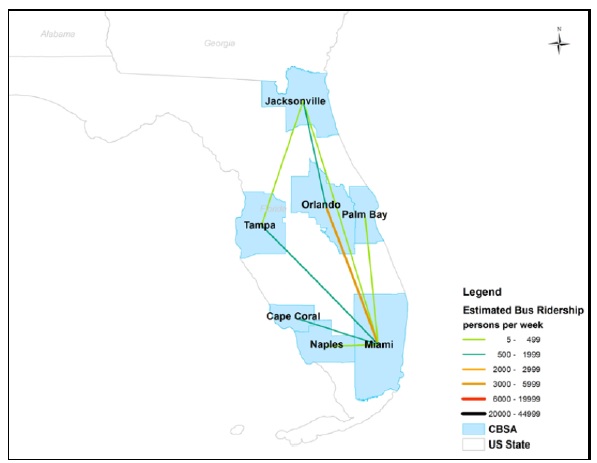

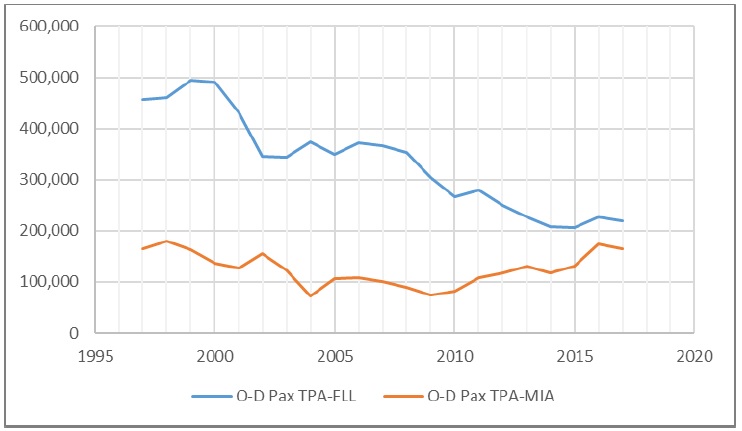

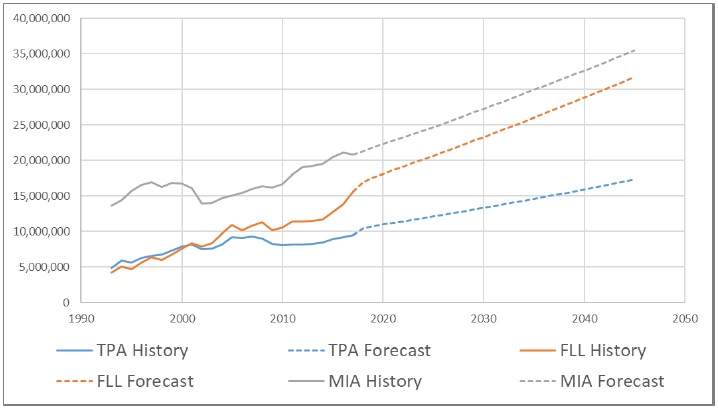

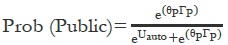

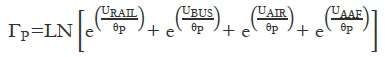

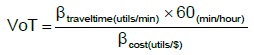

Source: National Association of Rail Passengers Amtrak Ridership Statistics, 2017